If Ace in the Hole is Billy Wilder at his angriest, then Bamboozled is Spike Lee at his angriest. It’s a scathing satire of the entertainment industry and the racism that underlines it. It’s all at once hilarious, thought-provoking, and uncomfortable to watch. I do recommend this movie frequently, but it’s definitely not for everybody. That said, it’s an important movie and deserves recognition, and so I’m going to talk about it anyway.

Pierre Delacroix (Damon Wayans) is fed with his boss and the television network he works for. He consistently pitches programs that feature intelligent Black characters, and is constantly turned down for their being too much like the Cosbys. His boss, named Dunwitty (Michael Rapaport), claims himself to be “blacker” than the Harvard-educated Delacroix and frequently uses the “n-word” in front of him. Desperate to escape his contract by being fired, Delacroix pitches the most offensive show he can think of, a variety minstrel show with the black performers in blackface and brings in two street performers to be his show’s hosts, Mantan and Sleep ‘n Eat. Their real names are Manray and Womack, and I’m stressing that now because I’m not about to refer to a character as “Sleep ‘n Eat” for the rest of this review. Womack is immediately put off by the show’s premise, but Manray sees it as his ticket to the big stage to show off his tap dancing talents, so they agree to do it. To Delacroix’s dismay, Dunwitty and the network are very enthusiastic about the show and it immediately becomes a hit, particularly white audiences, and so he changes his tune, declaring the show a satire and defending it, while his assistant, Sloane (Jada Pinkett Smith) is increasingly ashamed of it. An militant rap group, the Mau Maus, claim they will violently destroy the show if it’s not taken off the air immediately, though it is revealed that they originally auditioned to be the show’s in-house band. Womack quits the show, Sloane pushes to get it canceled, and after an argument with Delacroix, Manray also quits but is kidnapped by the Mau Maus as soon as he does and forced to tap dance on camera until he is shot. With everything in disarray, Delacroix retreats to his office where Sloane holds him at gunpoint in order to get him to watch a compilation of Black stereotypes from older Hollywood films and cartoons. They fight over the gun, Delacroix is shot in the process, and slowly dies as the montage plays.

I don’t think I’ve squirmed in my chair as much as during a scene before the show goes on air and they’re ramping up the crowd. White people fill the seats, covered in blackface, and cheer wildly, proudly proclaiming themselves as n****rs. It’s impossible not to laugh at the ridiculousness you see before you, but you also want to shut your eyes and ears. Though that montage at the end comes close on the cringe factor. It’s five unrelenting minutes of stereotypes that, on their own would make you inhale through clenched teeth, but in succession, are the equivalent of surgery without anesthesia. If you watch movies purely for entertainment value (which I am in no way knocking), steer clear of this one. It is entertaining, but that takes such a backseat to the message that it may as well be in the trunk.

I won’t deny my love for Spike Lee, though. He’s a director who is at his best when he’s angry, in my opinion. I know a lot of what he says is divisive, but you can’t deny the passion he puts into his arguments. And in Bamboozled, he’s got a bone to pick with just about everybody: Hollywood, the television industry, White people who cop Black culture, and even Black people who give up the culture for themselves. It’s brash and prickly, and I love the movie for it.

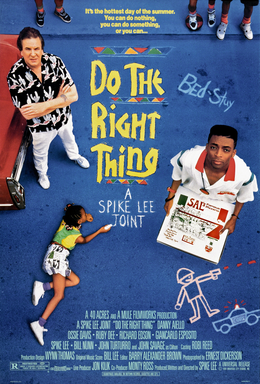

Bonus Review: Do the Right Thing

Here’s another Spike Lee Joint to marinate on, and it’s just and angry and relevant today as it was in 1989. On a hot summer day in Bed-Stuy, Mookie (Spike Lee, himself) is a pizza delivery man working for Sal Frangione (Danny Aiello), who owns a very Italian pizza shop in the predominantly Black neighborhood. One day, Mookie’s friend, Buggin’ Out (a young Giancarlo Esposito), enters the pizzeria and wants to know why Sal doesn’t have any Black people on his Wall of Fame, since his restaurant is in a Black neighborhood. Sal kicks him out. As the scorching day goes on, Buggin’ Out returns to Sal’s along with Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn), who is always carrying around his boombox with him, blasting music, and demands that Sal add some Black celebrities to his Wall of Fame. Tensions rise and Sal smashes Raheem’s boombox with a baseball bat. Raheem retaliates and they continue their fight outside, attracting attention from the neighborhood. The police show up and while attempting to restrain Raheem, an officer chokes him to death. Mookie, in a fit of anger or to keep Sal from facing the wrath of a mob (depends on who you talk to), throws a garbage can through Sal’s window, and the mob trashes and ignites it. After the fire department squelches the fire, a man named Smiley places a photo of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. shaking hands on what remains of the Wall of Shame. Mookie returns to Sal’s and, after a brief argument, the two seemingly reconcile.

The movie ends with the following two quotes:

“Violence as a way of achieving racial justice is both impractical and immoral. It is impractical because it is a descending spiral ending in destruction for all. The old law of an eye for an eye leaves everybody blind. It is immoral because it seeks to humiliate the opponent rather than win his understanding; it seeks to annihilate rather than to convert. Violence is immoral because it thrives on hatred rather than love. It destroys community and makes brotherhood impossible. It leaves society in monologue rather than dialogue. Violence ends by destroying itself. It creates bitterness in the survivors and brutality in the destroyers.”–Martin Luther King, Jr.

“I think there are plenty of good people in America, but there are also plenty of bad people in America and the bad ones are the ones who seem to have all the power and be in these positions to block things that you and I need. Because this is the situation, you and I have to preserve the right to do what is necessary to bring an end to that situation, and it doesn’t mean that I advocate violence, but at the same time I am not against using violence in self-defense. I don’t even call it violence when it’s self- defense, I call it intelligence.”–Malcolm X

Both of these quotes deserve analysis and reflection, but I don’t think that’s for me to do publicly. However, I will say that using the quotes in tandem do at least imply that there’s not a black and white answer to any questions that the movie raises. The most commonly asked question is apparently, “Did Mookie do the right thing?”, in reference to throwing the garbage can. I have my own opinions, but instead of sharing them, I’ll acknowledge that Spike Lee has commented on the question, reflecting that he is only ever asked it by White people, and that Black people never ask it. So, if you’re White like me, you may be asking, “Did Mookie do the right thing?” I don’t have an answer for you.