From 1937 to 2001, Disney had a stranglehold on animated films. There were small outliers during Mickey Mouse’s reign, namely the rise of Studio Ghibli and a string of very successful Don Bluth films with Amblin, but it wasn’t until DreamWorks came out with Shrek when we started to see the sands shifting. Shrek exploded at the box office and into the zeitgeist, and it’s no secret that Disney has never quite regained that spark that set them apart. DreamWorks, on the other hand, has maintained their status with successful franchises such as Madagascar, Trolls, How to Train Your Dragon and Kung Fu Panda (thanks to your aunt’s continued use of Minion memes on Facebook despite their drastic drop in popularity, Illumination is up there with them now, too. Side note: Can you believe they’re only on Despicable Me 4? I thought they were on the 10th one or something).

However, before Shrek, DreamWorks was struggling to find it’s voice. And by that, I mean that there was little consistency between projects and therefore no trademark for the studio, not that the movies weren’t good. In fact, partially because of that inconsistency, some of their very best films came out before Shrek. The Prince of Egypt, The Road to El Dorado and Chicken Run is a nearly-perfect three-film run, and if you want my honest opinion, The Prince of Egypt is not only the best DreamWorks animated film, it is also one of the Top 5 animated films of all time. It takes all of the youthful energy of a fledgling studio, along with the production sense of the three masters of their respective fields that make up the “SKG” below the DreamWorks logo, and swings for the fences. The result is an animated home run.

Apparently, the groundwork for The Prince of Egypt was laid way back when Jeffrey Katzenberg (Special Agent “K”) was still at The Walt Disney Company. He argued for an animated adaptation of the Charlton Heston classic, The Ten Commandments, but was repeatedly shut down by those above him because of Disney’s neutral stance towards religion. It was through the encouragement of Steven Spielberg (Agent “S”), at the founding meeting of DreamWorks, that set the film in motion. Agent “G” is David Geffen, by the way – as in Geffen Records. Anyway, more about the movie.

The Prince of Egypt is a blend of traditional hand-drawn animation and newer computer-generated animation, and uses both to great effect. The backgrounds and the characters are richly designed with significant attention to detail, and the spectacles of plagues and miracles are vibrant and fluid. My preference is hand-drawn animation by a wide margin, but there’s something to be said about what the movie was able to put to screen through a computer – the pillar of fire and parting of the Red Sea are particularly astounding. But that’s only scratching the surface.

Perhaps I should back up a bit. Show of hands, who does not know what The Prince of Egypt is about? And don’t just say “it’s about a prince in Egypt”. That’s obnoxious. Okay, well, for those of you who raised their hands, The Prince of Egypt is not totally an animated remake of The Ten Commandments. It’s a telling of the story of Exodus, with a little Charlton Heston thrown in. Fearing that his Hebrew slaves will be too numerous to keep in line, Pharaoh commands the killing of newborn Hebrew children. A woman named Yocheved isn’t letting them get her newborn son, so she sneaks to the river and puts the boy in a basket, sending it downriver and praying to God that nothing bad happens to him. Moses floats to where the river meets Pharaoh’s wife (daughter in the original text, but why introduce a character if you don’t have to?). Moses is adopted into Pharaoh’s family and raised as if he was of Pharaoh’s blood. This makes him the sort-of brother to Pharaoh’s biological son, Ramses. They grow up together, form an (almost) unbreakable bond, and chase each other through the streets of Egypt in chariots (thankfully, this is the most that gets pulled from The Ten Commandments). When Moses discovers his Hebrew heritage, he runs away (well, he takes the time to kill another man, first), becomes a shepherd, marries a pretty foreign lady with a name I’m not even going to attempt to spell, and lives a nice, quiet life away from high society. That is, until he starts hearing voices. God speaks to him through a burning bush, and tells him to return to Egypt and demand that the Egyptians (who have relied on slave labor for all their little wonders of the world projects, remember) let the Hebrew people go. Pharaoh says “no” at least seven times, which he eventually regrets, and then lets them go. Well, he changes his mind immediately and chases after the departing Hebrews with his entire army, but thanks to help from God, they get away by crossing a large body of water without a boat. Oh, and then Moses comes down from a mountain with ten commandments. The end.

The Prince of Egypt is relatively faithful to the Biblical account, but that’s only part of what makes it great. So much love and care went into this movie, and it’s clear in every second of film. Like John Hammond in Jurassic Park, they spared no expense. The film has an all-star cast, with the voice talents of Val Kilmer, Ralph Fiennes, Sandra Bullock, Jeff Goldblum, Michelle Pfeiffer, Patrick Stewart, Helen Mirren, Danny Glover, Steve Martin and Martin Short. Oh, and Ofra Haza, but I’ll get to her in a second. Val Kilmer, who voices Moses, also voices God in the burning bush scene in an attempt to move away from the big, booming voice of God from other films and treat it as more like “the voice you would hear in your head”, which I appreciate. Now, the absolute best part about this movie is the soundtrack. Every single song is fantastic, written and executed by Stephen Schwartz, whose works include Godspell, Wicked, Enchanted, and Disney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame. A stellar tracklist all the way down, but the most memorable of them all is the opening number, “Deliver Us”. It’s grandiose and yearning melody sets the mood for the film that you’ve just started with a powerful vocal from Ofra Haza. Not only was this woman a fantastic singer, but she sang “Deliver Us’ for 17 different dubs of the movie. I can barely get the words to “La Bamba” down. I have no idea how I could ever learn how to sing in 15 other languages. It’s astounding and a true testament to her talent.

Anyway, you get the idea. Don’t be put off by the fact that this is an animated movie and you’re a grown up who watches grown up movies. The themes in The Prince of Egypt and the weight they carry are a declaration that animated movies aren’t just for kids. There’s something in this movie for everyone to enjoy.

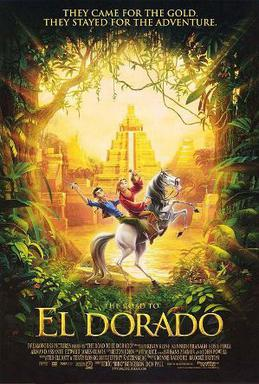

Bonus Review: The Road to El Dorado

The Road to El Dorado was released a little over a year after The Prince of Egypt, and like I alluded to before, is a very different movie. The film is meant to have a lighter tone, though it still does deal with adult situations such as sexuality, conquest and human sacrifice. The main inspirations for The Road to El Dorado are old swashbucklers (what is with my affinity for them?) and the series of Bob Hope and Bing Crosby movies. It’s full of action, excitement and comedy, and includes a great collection of songs from Elton John and Tim Rice (though they are admittedly not as good as their work for The Lion King).

Miguel and Tulio are two Spanish swindlers who end up making off with a map of “the New World” – a map that leads to El Dorado, “the city of gold”. A petty thief’s paradise. Miguel and Tulio sneak onto a ship to get to the Americas, and from there, follow the map. I don’t think it’s a major spoiler to say that they find El Dorado. However, they are immediately received with distrust by the locals, and their only way to get on their good side is to pretend to be gods the locals worship. Through circumstance, they convince nearly the entire city of their divinity, but it’s a ruse that’s hard to keep up. The High Priest, Tzekel-Kan quickly goes back to distrusting the two “gods” when they refuse his ritualistic human sacrifices. The chief of El Dorado may also not believe they’re gods, but he plays along when he sees how well the foreigners treat his people. With Tzekel-Kan snooping for proof that they’re lying and Hernan Cortes hot on their trail, Miguel and Tulio have to walk a thin line if they intend to stay alive.

The casting of Kenneth Branagh and Kevin Kline as Miguel and Tulio is inspired, and the majority of the songs are great (honestly, anything Elton John touches turns to gold). The movie is chock full of memorable scenes and lines of dialogue. Sure, it’s not as captivating as The Prince of Egypt, but The Road to El Dorado is fun and exciting, and I think every bit as deserving of people’s attention.