Casablanca is a movie that probably shouldn’t have worked as well as it did. It has a pretty star-studded cast, but it’s based on an unproduced play and the script was being written while filming was already underway. The script had three writers on it, and it was two against one the whole time. Paul Henreid, who played Victor Laszlo, apparently hated the rest of the cast. The movie is also more than the sum of its parts. The performances are good, the dialogue is mostly fine and full of famous lines, the story is decent but nothing special, but when it’s all put together and the movie fades to black, you’re left with a calming, resolute feeling in your heart.

Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart) owns and operates Rick’s Cafe in Casablanca, Morocco, and his door is open to everyone – French, American refugees, Nazis. He claims no loyalty to any political group, though he previously had a part in the Spanish Civil War. A thief named Ugarte (Peter Lorre) asks Rick to hold a couple of letters of transit he got from killing two German men until he can sell them, which Rick agrees to do. However, Ugarte is caught by local police captain Louis Renault (Claude Rains) and dies while in custody, taking the knowledge of the letters to his grave. Ilsa Lund (Ingrid Bergman), Rick’s former love, walks in and asks Sam, the piano player, to play “As Time Goes By”. Considering Ilsa ran out on Rick years ago, he’s less than happy to see her. It doesn’t help that she’s got her husband, Victor Laszlo, who is a fugitive resistance leader, with her. They could really benefit from some letters of transit. However, Rick isn’t too keen on parting with them after being spurned by Ilsa. Laszlo then convinces Rick to use the letters to take Ilsa to safety, knowing of their former romance while he was thought to be dead. Rick seemingly plans to do just that and have Laszlo framed for a crime in the process, but at the last minute, he sends Ilsa and Laszlo on the plane and walks away with Renault.

Everyone who sees it can admit that Casablanca is great, but what’s fascinating is that no one came seem to agree on why it’s great. At the time of its release, the United States had been involved in World War II for just over a year, so there was a heightened sense of patriotism in moviegoers that gravitated them toward Rick’s ultimate sacrifice. Over time, analysis of Rick’s sacrifice has shifted from the political to the personal, and a lot of emphasis gets placed on its status as a “classic”.

This sounds like I’m arguing why this movie doesn’t deserve to be on the list. It does. It’s a great story, a romantic drama with Nazi occupation in the background, but it’s a really good example of the effect time and culture has on the success of a movie. Casablanca received its accolades because it’s great. It exploded because of circumstance.

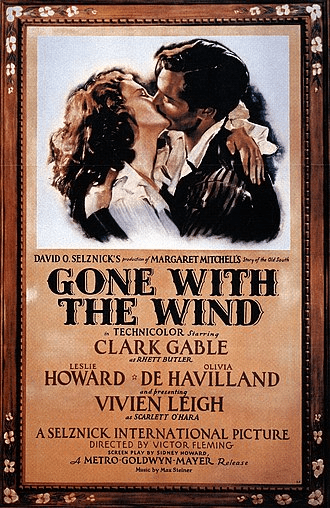

Bonus Review: Gone with the Wind

Gone with the Wind is a sweeping Civil War epic running just under four hours. But don’t worry your pretty little bladder, there’s an intermission, in case that’s a deterrent for you.

Gone with the Wind is the timeless tale of the love between a woman and her plantation. Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh, in the role she is rightfully known for) has the worst luck in the world. She loses her parents, three husbands, and two children (only one of these simply leaves, the others all die), she has to work and marry to keep her family’s plantation alive and in her possession, and the only person in the world who genuinely likes her is the wife of the man she loves (probably the worst of them all). Really, it’s the story of woman’s fight for survival at all costs, and despite her bad luck and the time in which she lives, she does it. It’s a romantic look at a very unromantic life.

Vivien Leigh puts in the performance of lifetime by bouncing between emotions, even within the same scene. She’s happy, sad, angry, distraught, flustered, excited and scared, all within the four-hour span. She and Clark Gable are obviously the focal point of the movie, but some of the supporting cast hold their own and keep themselves from being regulated to the background. Specifically, Olivia de Havilland and Hattie McDaniel. Hattie McDaniel even won an Academy Award for her performance, marking the first time an African American won the award. The film has a mixed reputation with the Black community for its portrayal of the slaves in personality and in perpetuating the “happy negro” myth. However, much has been said for Hattie McDaniel’s performance and subsequent win as some semblance of progress, though that’s still a point of contention. The head of the NAACP at the time referred to Hattie McDaniel as an “Uncle Tom” – a derogatory term that comes from the most egregious offender of the “happy negro” myth – but McDaniel replied, “I’d rather make seven hundred dollars a week playing a maid than seven dollars being one.”

Regardless of what’s outdated in the movie, it still holds up. It’s a story of determination and preservation, and should be viewed by everyone at least once. It’s a valuable piece of cinematic history and the highest grossing movie of all time, still, when adjusted for inflation.