No, I did not put 12 Angry Men here just for the Rush reference. It was purely coincidental. 12 Angry Men was Sidney Lumet’s feature film debut. He went on to make some of the greatest films of the 60s and 70s, including The Fugitive Kind, The Pawnbroker, Fail Safe, Serpico, Murder on the Orient Express, Dog Day Afternoon, and Network, but what a start. Now, considered one of the greatest films of all time and the second-greatest courtroom drama, just behind another film that we’ll get to later, 12 Angry Men is a simple story constructed from a teleplay. Because of this, there are only four filming locations in the entire movie: the courtroom where the tail end of the trial occurs, the jury room where the majority of the film takes place, the jury bathroom for one conversation, and outside the courthouse for one final, brief conversation. It’s a very contained film, and Lumet uses that fact to great effect. When the deliberation in the jury room begins, the camera is pulled back and the characters are viewed from further away, but as the film gets more intense, the camera zooms in until the characters are all viewed in close-up. It’s an intentional dose of claustrophobia that only elevates the movie higher up.

On a hot day in New York, a jury is tasked with deciding the fate of a poor 18-year old who is accused of killing his abusive father. The judge tells the jury that if there is any reasonable doubt then the jury must vote “not guilty”, and because a “guilty” verdict will result in the electric chair, voting must be unanimous. At first, the case seems cut and dry: there are witnesses to seeing the stabbing, hearing the boy say he will kill his father, and seeing the boy run out of the apartment. He also had purchased a switchblade just like the one found at the scene of the crime, but claims to have lost it. The jurors immediately hold a vote to see where they stand and it is near unanimously “guilty”. Only Juror 8 votes “not guilty” just to ensure they discuss the case more. There is some discussion, but even when Juror 8 produces a switchblade that looks exactly like the murder weapon (which was thought to be one-of-a-kind), the others are not convinced. Juror 8 tells the others to hold a secret ballot and he will abstain. If the rest are “guilty”, he will change his vote. However, there is a single “not guilty” in the secret vote. Juror 9 confesses he agrees there should be more discussion. Over the course of the day, the jurors look at each witness’s account and slowly poke holes in their stories. One by one, the jurors develop a reasonable doubt in the case and change their votes. Juror 3 remains the last holdout and goes on a rant, trying to prove his point, only to realize his own strained relationship with his son is informing his views of the case. He changes his vote and the jurors leave. As they go, Juror 8 helps Juror 3 put his coat on.

The film consists mostly of just the 12 angry-ish men. As the one holdout, Juror 8 is played by leading man, Henry Fonda, but the rest of the cast is rounded out by mostly character actors who you might have seen in other things and not realized it. Juror 1 is Martin Balsam (On the Waterfront, Psycho, Breakfast at Tiffany’s and episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Twilight Zone, Have Gun – Will Travel, and The Untouchables). Juror 2 is John Fiedler (A Raisin in the Sun, That Touch of Mink, True Grit, as well as the voice of Piglet on Winnie-the-Pooh). Juror 3 is Lee J. Cobb (On the Waterfront, How the West Was Won, The Exorcist, and episodes of The Virginian and The Young Lawyers). Juror 4 is E. G. Marshall (The Caine Mutiny, Tora! Tora! Tora!, National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation and episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Rawhide, and The Defenders). Juror 5 is Jack Klugman (Cry Terror!, Days of Wine and Roses and episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Gunsmoke, The Twilight Zone, The Fugitive and The Odd Couple). Juror 6 is Edward Binns (North by Northwest, Judgment at Nuremberg, and Patton). Juror 7 is Jack Warden (From Here to Eternity, Donovan’s Reef, Shampoo and All the President’s Men). Juror 9 is Joseph Sweeney (The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, The Fastest Gun Alive and episodes of Car 54, Where Are You?). Juror 10 is Ed Begley (Odds Against Tomorrow, The Unsinkable Molly Brown and episodes of Route 66, Rawhide, The Dick Van Dyke Show, Gunsmoke and Bonanaza). Juror 11 is George Voskovec (The Bravados, BUtterfield 8, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, and The Desperate Ones). And finally, Juror 12 is Robert Webber (Harper, The Dirty Dozen, Midway and episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Route 66, and The Fugitive). The end.

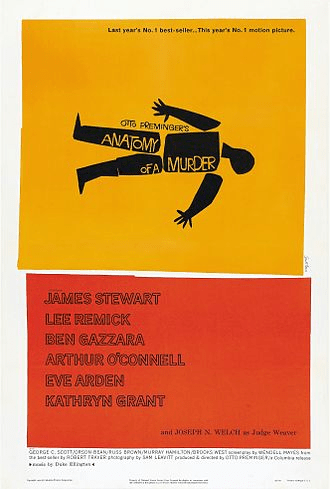

Bonus Review: Anatomy of a Murder

One of the biggest criticisms of the courtroom drama is how unrealistic it is from a legal standpoint. Real lawyers aren’t allowed to raise their voice in the courtroom, or call surprise witnesses, and they don’t object as often as the movies would make you think. There’s no “You can’t handle the truth!” moments. However, Anatomy of a Murder is true to its title and an accurate portrayal of the defense process, so much so that it is used in law schools as a teaching tool. How many movies can you say are two-hour-and-forty-minute crash courses in law?

Paul Biegler is a small-town lawyer and a former district attorney. He is hired to defend Lieutenant Manion, who shot and killed an innkeeper named Barney Quill. Manion admits to the murder, but says it was in response to Quill raping his wife and doesn’t remember the actual course of events. Even with the irresistible impulse (temporary insanity) defense, it’s still an uphill battle for the trial. The prosecution also fights to keep Manion’s motive out of the courtroom, but Biegler convinces the judge to admit it. The one witness to the murder, the bartender, Al Paquette refuses to cooperate with the defense, either because of loyalty to Quill or a love for Quill’s secret illegitimate daughter, Mary. Mary is thought by the prosecution to be Quill’s lover since her true connection to Quill is hidden for her own benefit. Biegler talks Mary into getting Paquette to comply, but even that is a fruitless endeavor. Manion’s wife claims that Quill tore off her underwear during the rape, but the underwear is nowhere to be found. When Mary hears this, she testifies that the underwear was found in the inn’s laundry room the morning after the alleged events. The prosecution tries to argue Mary’s testimony as that of a jealous lover, forcing her to admit to being Quill’s daughter. Manion is found not guilty by reason of insanity.