The Silence of the Lambs did a bad, bad thing. It ignited a love affair between American audiences and serial killers. Before this film, serial killers were a slasher exclusive like Michael Myers, Leatherface, and Jason Voorhees – masked or disfigured monsters who killed without purpose. But The Silence of the Lambs introduced two new types of serial killers – the genteel and soft-spoken Dr. Hannibal Lecter and Jame Gumb, or “Buffalo Bill”, who Jonathan Demme (the film’s director) is quoted as labeling “a tormented man who hated himself and wished he was a woman because that would have made him as far away from himself as he possibly could be.” Maybe some of those other slashers felt the same way, but in The Silence of the Lambs, we are given that look into the man behind the monster, so to speak, that these other movies just don’t give us. They aren’t intended to.

Clarice Starling is a young FBI agent that gets involved with a string of murders by being asked to interview known cannibal, Dr. Hannibal Lecter, to get a profile on the alleged culprit, Buffalo Bill, a serial killer that only attacks women and takes some of their skin before disposing of the bodies. At first, Lester rejects her questions, knowing Starling’s superior’s true motive, but when another inmate at the Baltimore State Hospital for the Criminally Insane flings his bodily fluids at Starling, Lester changes his mind, gives her a clue, and somehow convinces the other inmate to swallow their tongue overnight. Lecter agrees to profile Buffalo Bill in exchange for a transfer to another hospital because he hates the administrator at this one. Starling’s supervisor tells her to go along with the idea, but it’s a fake deal. However, when a senator’s daughter is Buffalo Bill’s next victim, she uses her power to get Lecter out to Tennessee where he gives her an accurate description of Bill, but calls him “Louis Friend”, which is another code for Starling to decipher. Starling visits Lecter in Tennessee and he confirms her deduction of the clue and also returns the case files with his notes. Later that evening, Lecter escapes his containment by cutting the face off one of his guards to use as a mask. Starling follows Lecter’s notes to Bill’s first victim, whom he apparently knew. She realizes Bill is Jame Gumb and tells her superior who leads a team to his listed address. However, the house is empty. But Starling follows the notes to a different address and realizes the man who answers is Buffalo Bill. She tries to arrest him, but Bill shuts the power off in the house and uses night-vision goggles to stalk Starling. She’s completely blind in the dark, but hears Bill cock a pistol and successfully shoots him first. She also finds the still-alive senator’s daughter.

This Oscar-winning film keeps you on the edge of your seat throughout and only heightens its intensity in its climax. When the lights go out, you will be clenching cheeks without question. Anthony Hopkins as Hannibal Lecter is a force of nature. He’s the most recognizable and influential part of the movie, and he’s only onscreen for 16 minutes. This has to be in part due to the contradictory nature of the character, inspired by the “criminal doctor”, Alfredo Ballí Treviño. Buffalo Bill also uses some real-life inspiration. Both Gumb in this movie and Norman Bates in my previously-reviewed Psycho take a lot of inspiration from real-life serial killer, Ed Guinn, as well as a few other similar killers, all of whom were known to use the skins of their victims to make body suits or furniture. It’s horribly grotesque and disturbing, but that’s partially what makes it so fascinating. And in recent years, the obsession with true crime stories has skyrocketed to new heights. Just check your local bookstore or the popular content of a streaming service. We’re fascinated with the macabre, especially when it’s real. That true-life comparison and its proximity serve to inflame our fear, making The Silence of the Lambs truly terrifying.

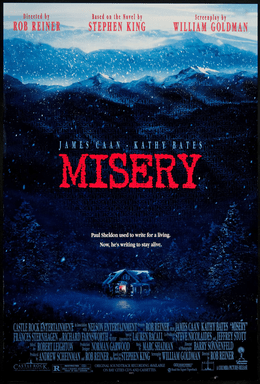

Bonus Review: Misery

From the director of This is Spinal Tap, Stand By Me, The Princess Bride, and When Harry Met Sally… and the screenwriter behind Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Marathon Man, All the President’s Men, and The Princess Bride, comes a movie unlike of those others: Misery. This adaptation of the Stephen King novel is considered one of the best, even from the author himself (he famously despised Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining). The movie also introduced the world to Kathy Bates (she had been in films for nearly 20 years prior, but always in small bit roles; after Misery, she was a household name). The premise is simple: an author is rescued by his number-one fan and is kept at their house and forced to write a novel he doesn’t want to. Kathy Bates’ Annie Wilkes is simultaneously a personification of drug and alcohol dependency and fandom’s ability to pigeonhole creatives. Again, simple, but powerful and personal – not just to King, but probably to everyone involved in the film adaptation too, since Bates was not a star and Reiner and Goldman were not associated with the horror genre up to that point.

Paul Sheldon is a famous author who has spent most of his career on a series of romance novels following a character named Misery Chastain. He hopes to break away from the Misery series by killing her character in one final novel. After he finishes the manuscript in a secluded Colorado cabin, he begins to drive home. However, a blizzard knocks him off the road and he falls unconscious. When he awakes, he is in a bed with two broken legs and a dislocated shoulder. Annie Wilkes comes into his room and explains that she found him and is nursing him back to health until the roads and telephone lines reopen. She also just happens to be his number-one fan. Annie displays odd behavior throughout their conversations, but it comes to a head when Paul lets her read his manuscript and she learns of Misery’s fate. She unleashes a verbal fury on him and admits that no one knows he’s at her house. Annie makes him burn the manuscript and begin writing a new Misery novel with a better ending. After finding a bobby pin, Paul is able to sneak out of his room when Annie’s not around. He finds a scrapbook of newspaper clippings that indicate Annie was put on trial for the deaths of several infants at the hospital where she worked. She was acquitted for lack of sufficient evidence, but Paul reads where she quoted Misery during her trial. Annie notices a figurine out of place from Paul’s wondering, and to prevent him from sneaking out again, breaks his ankles with a sledgehammer. The local sheriff comes snooping around as he investigates Paul’s disappearance, but Annie kills him. She will let Paul finish the new novel and then she plans to kill them both. During a brief stint in the basement, Paul hides lighter fluid on his person and then uses it to burn the finished manuscript in front of Annie before she can read it. They fight, but Paul is able to kill her using a metal doorstop. Some time later, Paul enters a restaurant to meet his agent. A waitress comes by, recognizes Paul, and claims to be his number-one fan.