Are you not entertained? How could you not be when watching Gladiator? Russell Crowe became the talk of the town for his role of the father to a murdered son, husband to a murdered wife, Maximus Decimus Meridius. With direction from Sir Ridley Scott and a background of Hans Zimmer music, Crowe Spartacuses his way into our hearts and our dreams. There is nary a man in high school or college at the time of this movie’s release who did not want what they did in life to echo in eternity. Though a story of revenge, Maximus is made sympathetic and all too human, which is why we like him, but he is also superhuman when he needs to be, which is why we want to be him. We’ll see if our protagonist is half as likable in the sequel.

Maximus begins the film a Roman general on his way home from a victory over the Germanic tribes, but first he makes a stop at his boss’s house, Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Marcus Aurelius tells Maximus that his son, Commodus, is not fit to rule and so he intends to let Maximus rule as regent when he dies so he can restore the Roman Republic. However, after Maximus leaves, an obviously upset Commodus murders his father. Unfit to rule, indeed. Commodus proclaims himself Emperor and demands fealty from Maximus. Maximus refuses, so Commodus demands he and his family are to be killed, and he is immediately arrested by Quintus, leader of the Praetorian Guards. Maximus kills his captors, but is wounded in the fight. He ignores his injuries and grabs a horse, racing home to his family, but when he arrives, they are already dead. Maximus buries them and then collapses from his wounds. He is picked up by slave traders and sold to gladiator trainer, Proximo. Because of his training as a Roman general, Maximus easily wins his fights and is given the nickname, “the Spaniard”, by the people who cheer him on. He befriends Juba, another gladiator. Proximo learns that Commodus is planning a celebratory 150 days of gladiator fights in honor of his father (but really to gain the love of the Roman people), and so he tells Maximus that he can possibly win his freedom if he “wins the crowd”. Maximus disguises himself with a helmet so Commodus does not recognize him as he fights, but after a victory, Commodus demands that he removes it. Upon doing so, Maximus declares he will have his revenge. Commodus does not kill Maximus due to the love of the Roman people.

Commodus arranges to have Maximus duel an undefeated gladiator named Tigris, in hopes of getting him taken care of in the coliseum. However, Maximus defeats Tigris, and when he is ordered to finish him off, Maximus refuses. The crowd cheers him as “Maximus the Merciful”. Commodus fears that killing Maximus will turn him into a martyr. Maximus learns that his former legions remain loyal to him and he devises a plan with Lucilla (Commodus’ sister whom he has incestuous feelings for) and Gracchus (a Roman senator, who will be in power if the Republic is restored) to get out of Rome and rendezvous with his men. When word of the conspiracy reaches the ear of Commodus, he orders the Praetorian Guards to attack the gladiator barracks. Proximo and some others fight off the guards, giving Maximus the chance to escape, but Maximus is captured soon after. Commodus challenges him to a duel in the colosseum, hoping that a victory will regain the public’s favor. However, before the match begins, Commodus stabs Maximus to give himself an advantage in the fight. Surely that’ll win the public back. Maximus is still able to disarm Commodus in the fight, and when his own guards refuse to help him, Commodus pulls a knife on Maximus in a last-ditch effort to kill him. Maximus, however, successfully turns the knife on Commodus, killing him. Growing weak from his wounds, Maximus quickly demands the restoration of the Republic. As he dies, he envisions reuniting with his family in the afterlife. Lucilla gives him the honor of being carried out of the colosseum as a “soldier of Rome”.

I won’t say much about the film’s historical inaccuracies because Ridley Scott is indifferent to them and they never have any bearing over whether a film is good or not, but I will point out two things I discovered about gladiator stuff that I found interesting. First, the thumbs up/thumbs down thing Commodus does in the film is backwards. In real life, the thumbs up represented a ready blade, which meant to kill the defeated. The thumbs down represented a sheathed sword and meant the gladiator would be spared. Secondly, apparently gladiators had product endorsements, much like our athletes do today. They were originally going to make this fact part of the film, but decided against it, thinking it too unbelievable for audiences. Honestly, that was probably the right call.

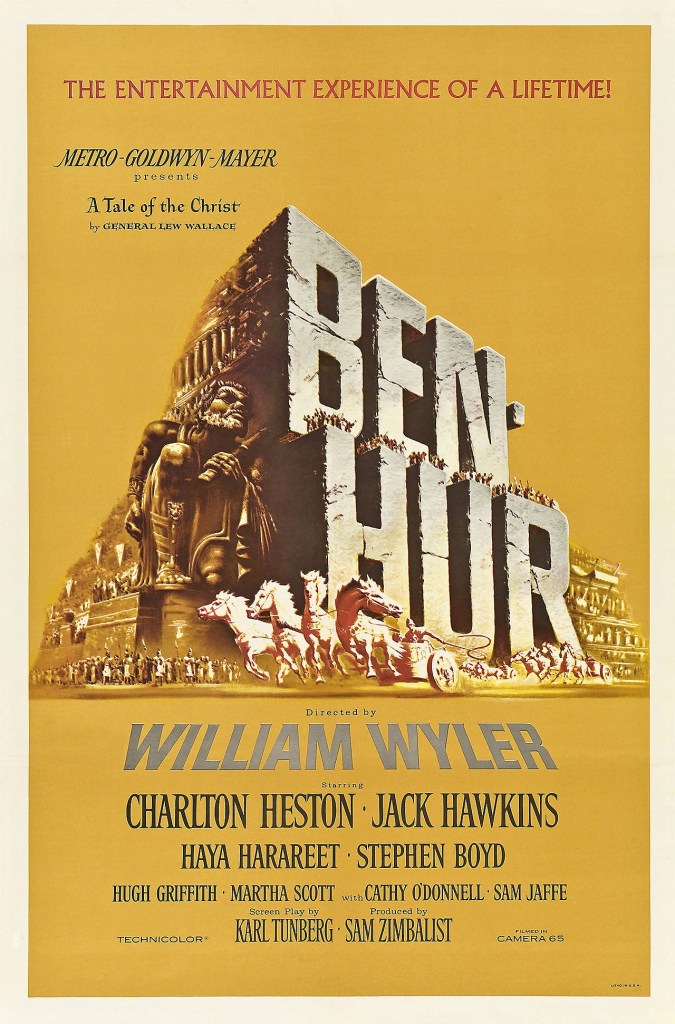

Bonus Review: Ben-Hur

Ben-Hur is a four-hour epic about a man who just wants to get back to his family. Judah Ben-Hur spends time in prison, as a galley slave, and a charioteer before successfully returning home. Throughout the trials that Judah Ben-Hur endures, he grows increasingly angry, fueling his hate for the man who betrayed him until it consumes him. Jesus Christ appears four times in the story, mostly in the background – his birth, a scene at a well where he gives Judah a drink of water, when he preaches the Sermon on the Mount, and his crucifixion, where Judah recognizes him as the man who gifted him water so long ago and attempts to return the favor. It is the crucifixion where Christ comes to the forefront, and acts as the ending to the film. At seeing Christ on the cross, Judah Ben-Hur’s rage dissipates.

A lot has been said about the film’s exciting chariot race scene. The stunt work from Yakima Canutt is excellent and the scene is edited so quickly that it offers a rapid-fire delivery to the screen, and it has rightfully been analyzed by film students and critics everywhere. However, one of my favorite aspects about Ben-Hur is something that doesn’t appear on screen: the face of Christ. Art, for millennia, has concerned itself with the appearance of Christ, and Hollywood is no exception to this, despite what certain political pundits would tell you. Just look at other biblical epics from the same time period: The Robe, The Greatest Story Ever Told, and King of Kings. All of these – and then some – concern themselves with a depiction of Jesus. But Ben-Hur refuses to do it. It’s probably because Ben-Hur is as much a Jewish story as it is a Christian one, but I like to believe – even if it is a symptom of placating two different groups – that it’s intentional reverence.