The ultimate summer blockbuster. Only Steven Spielberg’s third film, Jaws shot him to the stratosphere as well as revitalized the Monster movie genre. When a great white shark terrorizes the beach of a coastal town, the new police chief, Martin Brody (Roy Scheider), closes the beaches. The heartless mayor is on his case about keeping the beaches closed, as he fears the town’s economic suffering for the summer months. Instead, a bounty is placed on the shark, and when the many would-be bounty hunters fail at bringing the shark down, it’s up to Brody, Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss), and Quint (Robert Shaw) to save the local waters. You know the movie. You know the soundtrack. The movie and specifically the image of just a shark fin gliding across the water has been parodied and referenced to death, but that just proves its longevity.

Jaws was originally offered to another director, Dick Richards (if you don’t recognize the name, I’m not surprised; he directed a total of seven films in a 14-year span and none of them hits). Richards was reportedly kicked off the film for unintentionally aggravating the producers by constantly referring to the shark as a “whale”. After Richards was dismissed, Spielberg (who had lobbied hard for the job) was given a shot, even though his theatrical film debut, The Sugarland Express, had yet to be released and was therefore only known for directing episodes of television such as Night Gallery and Columbo. It was a gamble that paid off for everyone involved as the movie made a return of $476.5 million on a $9 million budget, and Steve Spielberg became a household name and jump-started his career off the notoriety that came with Jaws. Even more of a gamble due to all the delays the film underwent in filming because of Spielberg’s to film on the ocean instead of in a studio. Originally, the film was on a $4 million budget, but the weather and shark malfunctions ballooned it to the $9 million figure I mentioned earlier. The shark malfunctions also led to the smartest creative decision in the whole movie.

Alfred Hitchcock famously gave an example on the difference between “suspense” and “surprise” by discussing a theoretical bomb going off in a film. If the bomb is not addressed before the explosion, then there is a brief shock to the audience, a surprise. But if the bomb is established well before it goes off, everything else in the scene is more exciting because the audience knows what’s coming, and is therefore in suspense. He ended the example with the following statement: “There is no terror in the bang, only in the anticipation of it.” I bring this quote up not just because it’ll make sense for the bonus review, but it makes sense for Jaws as well. Spielberg seems to have taken this quote to heart because you don’t see the shark in full until around an hour and twenty minutes into the movie. Before that, you only see the infamous fin, and it makes it that much more suspenseful. We know it’s a shark, but to not actually see it for so long a time…it just kinda gives you the heebie-jeebies thinking about what could be in the water. It makes for a significantly more exciting movie, and it never would have happened if it weren’t for problems with the mechanical shark.

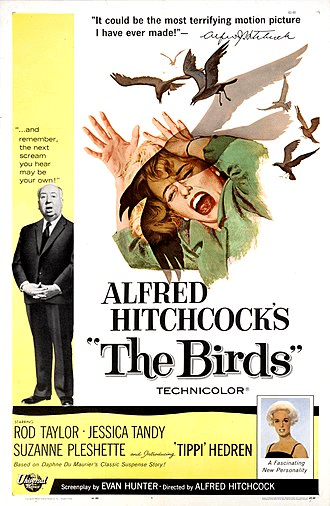

Bonus Review: The Birds

This is Alfred Hitchcock’s third adaptation of a Daphne du Maurier story. What was his obsession with that woman? Already he had made Jamaica Inn and Rebecca – two films that simultaneously indicated the end of his British moviemaking career and the beginning of his American moviemaking career. Jamaica Inn brought Maureen O’Hara to the world’s attention and Rebecca received many accolades, including the distinction of being Hitchcock’s only film to win the Oscar for Best Picture. Despite these credentials, The Birds is the most well-known of the three.

The Birds starts off as a romantic comedy, surprisingly. And it follows Mitch and Melanie who fall in love through happenstance and despite Mitch’s overbearing mother. Things take a turn, however, when bird attacks start happening randomly. Mitch and Melanie struggle to keep themselves and Mitch’s mother and sister safe during the attacks. During a scene in the attic of Mitch’s house, Melanie is attacked and must be rescued. Her wounds and catatonic state cannot be treated at Mitch’s house, so Mitch, his mother and his sister slowly and quietly lead Melanie out to the car and drive away as the birds watch them go. The film never explains why the attacks start or why they stop, or if they even have stopped.

The Birds is not as critically well-received as other Hitchcock films, and that’s probably because of the strange tonal shifts and the lack of conclusion. Although, those are fair criticisms, while the movie is happening, those thoughts will be the furthest from your mind. As mentioned above in my review of Jaws, Hitchcock applies his theories on suspense to this film. Particularly, there is a scene where Melanie is waiting outside of a school to pickup Mitch’s sister, Cathy. As she sits in her car, the audience sees as crow after crow lands on a nearby jungle gym, though Melanie remains oblivious to it. No attacks happen right away, but the audience can see what’s coming, and it’s executed perfectly. The Birds is not Hitchcock’s best by a long shot, nor is it a movie worth defending if the claims Tippi Hedren has made regarding her treatment by Alfred Hitchcock are true, but it is an enjoyable film and a great addition to the canon of both monster movies and natural disaster movies.