Ingmar Bergman spent the majority of his life in a state of limbo. He was plagued with philosophical questions that seemed void of answers, and as his filmography portrays, he would never find answers within his lifetime. Raised by his Lutheran minister father in a strict household, Bergman was surrounded by religion and the matters of the spirit. However, as many do in such an environment, Bergman claims to have lost his faith at a young age and spent the rest of his life reconciling that. Because of this, several of his films are plagued with attempts to reconcile a loving God with a cruel, cold existence – i.e. “Why would a loving God allow evil in the world?”, or maybe more emphatically, “Why would a loving God remain silent when there is so much evil in the world?” For The Seventh Seal, Bergman uses the backdrop of a time when religious themes were ever-present within art and literature: The Middle Ages.

The plague has made its way through Denmark when Antonius Block and his squire return home from the Crusades. Block is met by Death in a black cloak along the road and invites him to a chess game, in hopes to prolong his life. Block and his squire visit a church where an artist is painting a variation of the Danse Macabre (the Dance of Death) on the ceiling. While at the church, Block visits the confessional and tells the priest he views his life as pointless up to present and hopes to live long enough to perform one good deed. The priest tells Block of a chess move that will help him defeat Death, but Block realizes that it is actually Death on the other side of the confessional and leaves. A family of actors perform in the village, but there show is interrupted by a group of flagellants. The actors and Block flee the village and have a picnic in the countryside. When they see the effects the plague is having on the people, Block offers to let everyone shelter at his castle until it passes. At one instance, the husband in the acting troupe sees Block playing chess with Death and attempts to flee. Block uses the chess game to distract Death and knocks over the pieces while the acting family sneak away. Death resets the board exactly as they had it and finishes the game, winning. He asks Block if he has accomplished his good deed and Block says he has. Death appears again during supper as a storm is passing over the countryside. The acting family watch from their sheltering spot as Death leads Block and his other guests in the Danse Macabre.

The title of the film comes from Revelation, chapter 8 and verse 1, which says, “And when he had opened the seventh seal, there was silence in heaven about the space of half an hour.” Given the subject matter and themes of the film, it’s an apt title. The time of the plague was considered by those who lived through it a sign of the end times – the time of Revelation – and that “silence in heaven”, in the context of the movie, is attributed to God. There are some Bergman films that treat religion fairly cordially, and then there are others, like The Seventh Seal, that treat it with great disdain. All of the religious characters, except for Block, are incredibly wicked and are rapists, self-mutilators and witch hunters. Death, himself, assumes the role of the priest in the confessional. However, despite what I think was his intention, Bergman cannot help but portray some religious ideas in a positive light. The family of actors are viewed as innocent and are therefore allowed to escape Death, and along with that, Block’s way of saving the family is an act of self-sacrifice. It was his one good deed. On the whole, The Seventh Seal and much of Bergman’s filmography is hopeless and depressing, but it is specifically because of that fact that the moments of goodness and holiness shine as brightly as they do.

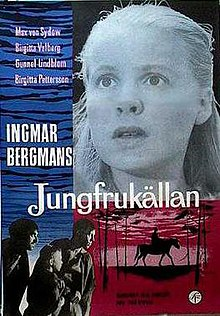

Bonus Review: The Virgin Spring

Another film from Ingmar Bergman set in the Middle Ages. The Virgin Spring, for me, is constantly in contestation with The Seventh Seal for the spot on this list. The Seventh Seal edges this one out mostly because of its iconic imagery and what it did for bringing attention to World Cinema in the United States. However, thematically, I prefer The Virgin Spring, which operates on two fronts: 1. A dissection of guilt within the individual, and 2. The battle between Christianity and Paganism for dominance in medieval Sweden. The film also draws heavy inspiration from another Bonus Review I did not too long ago – Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon.

Based on a 13th-century Swedish ballad, The Virgin Spring is about the legend of a pious Christian man named Per Tore. Tore sends his daughter, Karin, to travel a day’s journey to church to provide candles for an upcoming service. Karin brings along Ingeri, one of the family’s servants who worships Odin and is pregnant out of wedlock. Ingeri becomes frightened when they approach a mill near a stream. Karin decides to press on without Ingeri, and runs into a trio of herders – two men and a boy – who ask Karin to sit and have lunch with them. Ingeri tries to meet up with Karin, but arrives on the scene as the two men rape and murder Karin, so she hides. The herders take Karin’s clothes and seek shelter at Tore’s house. After supper, one of the herders tries to sell Karin’s clothes to Karin’s own mother. She locks the herders in their room and tells Tore what she suspects happened. Around that time, Ingeri returns home, breaks down, and tells Tore everything she witnessed. She also confesses she had secretly prayed to Odin for Karin’s death out of jealousy. At the crack of dawn, Tore enters the room and kills all three of them, including the boy. Afterwards, Tore and his family follow Ingeri to where Karin lays. Tore cries out to God and promises to build a church at the very spot where Karin died. As he lifts her body to carry her home, a spring sprouts from the spot and flows downhill to meet the river. Ingeri washes herself in the stream.

The Virgin Spring loves to play with both Christian and Pagan imagery. At the mill, a one-eyed man appears to Ingeri – a likely reference to the Norse god, Odin – who in the film seems to act as a stand in for the Devil. Also, when Tore decides to take revenge and kill the herders, he tears down a tree with his bare hands to block the door so the men can’t escape. The tree, a symbol for Pagan worship, indicates Tore’s brief abandonment of his Christian faith and chooses vengeance over forgiveness. Ingeri’s bathing in the stream at the end is a clear reference to the act of baptism, a ritual that some Christian sects believe absolve you of your sins. That stream coming from where Karin lays, where she lost her innocence, is particularly poignant. The Virgin Spring is a beautifully told period drama that more accurately portrays the Middle Ages than most films and is atmospheric and absorbing for its audience.