The following was taken from a full-length review I wrote on this website on 09/05/2023.

I recently watched this film again, also through the Criterion Channel, after not having seen it since college. I remember when I watched it that first time and thinking, “This movie looks cheap. New York City looks so grimy, and the camera is all over the place.” At that time, I naively considered these flaws of the filmmakers, and enough to make me dismiss the film as a whole. Obviously, I have since changed my tune. Those things still remain, but some are due to budgetary restrictions and therefore cannot affect the merit of the movie as a whole, and some are stylistic choices. Most Scorsese gangster movies have a crisp look to them. NYC isn’t the problem, it’s the people who are grimy. Mean Streets informs us that it’s both, and that, in part, was the intention.

Charlie (Harvey Keitel) is a good boy – he works for his mafia-connected uncle, and therefore has to do some unsavory things, but he’s very concerned with his sense of morality and the salvation of his immortal soul. So concerned that, every time he sees fire, he tries to touch it in hopes he can withstand the heat. Anyone who has ever touched a hot stove knows that doesn’t go well for him. Since the Catholic Church will not absolve him of his sins without him actually confessing them, he attempts to earn his salvation another way.

Enter Johnny Boy, played by a nearly brand-new Robert De Niro. Johnny Boy is the cousin of Charlie’s epileptic girlfriend, Teresa, but more importantly, he’s a ne’er-do-well on the path to eternal damnation. Charlie sees Johnny Boy as his ticket to Heaven. If he can get Johnny to walk the straight and narrow, there’s no way Saint Peter would turn him away. The only problem is that the more Charlie interferes with Johnny Boy’s erratic way of living, the worse it gets. Johnny Boy feels coddled. Some people just don’t want to be saved. His antics not only set his life on a downward spiral, but he begins taking everyone else down with him – particularly Charlie. It all comes to a head in a drive-by shooting in those mean streets. Johnny Boy, Teresa and Charlie are all hurt, but Johnny Boy walks away into an alley where the red, flashing lights of a police car hint at his final destination, and Charlie walks out into the street, baptized in the waters of a broken fire hydrant. Only Teresa is unable to get out on her own, more damaged than the others, requiring the EMTs that get to the scene first to help ease her out of the car. Teresa and Charlie will survive, but while he kneels in the street, and images of the sinful life he is potentially leaving passes before his eyes, Charlie doesn’t even acknowledge the condition Teresa is in. And in that moment, that final scene, we understand how selfish Charlie’s quest to earn his own salvation truly is.

As I said before, my views on this film have changed significantly. Where as once I held Mean Streets with slight disdain, even considering it lower-tier Scorsese, I have now nearly flipped that completely. Mean Streets isn’t just a great film, it’s also pure Scorsese, through and through. It’s full of Catholic guilt, religious imagery (a chat between Charlie and Johnny Boy in a graveyard, where Johnny lays on a grave and Charlie leans against a cross, is particularly excellent), an internal wrestle between saint and sinner, a killer 60s pop soundtrack (one of the first examples of a jukebox soundtrack; the infamous bar brawl scene is set to the Marvelettes’ “Please, Mr. Postman”), tracking shots (that same bar brawl), and a whole lot of New York City.

I read that Scorsese wrote the screenplay for this film (not something he does often) after a talk with actor/director John Cassavetes, where Cassavetes criticized his previous film, Boxcar Bertha, for being uninspired. His advice to a young Scorsese was to make films he’s passionate about. You can feel the passion in Mean Streets. I argue you will not find a film so near and dear to Scorsese’s heart again until 2019’s The Irishman. It’s reflective and thoughtful. It’s genuine. It’s a filmmaker in the middle of insecurity, discovering his voice and, somehow, confidently firing on all cylinders. Martin Scorsese’s third film is, dare I say, a masterpiece, and sits alongside Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, and GoodFellas in the discussion for his best.

Bonus Review: All That Money Can Buy

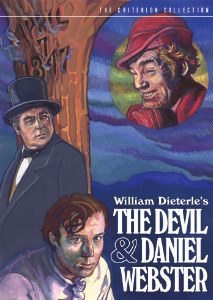

I promise the photo matches the film I’m reviewing. Originally titled The Devil & Daniel Webster, the movie was renamed All That Money Can Buy so as not to confuse audiences with another release the same year: The Devil and Miss Jones. It later regained its original title when rereleased. However, just a few years ago, it was restored for the sake of preservation by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, and since then has been presented as All That Money Can Buy, so that’s the one I’m going with. It’s the same movie, either way. I just thought I’d share.

First, a history lesson. Daniel Webster was a New Hampshire lawyer, orator and served as the US Secretary of State under Presidents Harrison, Tyler and Fillmore. He was strongly opposed to the War of 1812 and argued in the Supreme Court cases McCulloch v. Maryland and Gibbons v. Ogden. He unsuccessfully ran for President multiple times. His biggest claims to fame are his involvement in the Compromise of 1850 and a congressional speech he made in 1830, titled, Second Reply to Hayne. His prominence made him nationally known and liked by both sides of the political spectrum. I presume it’s these two factors that put Daniel Webster into the short story by Stephen Vincent Benet that the movie is based on.

Jabez Stone is a poor farmer in New Hampshire in 1840 who happens to have the worst luck you can imagine. After a string of particularly terrible things occur to Jabez, he exclaims that he would sell his soul to the Devil for just two cents, and wouldn’t you know it, not two seconds later, a man calling himself “Mr. Scratch” comes by with a very enticing offer: in exchange for his soul, Jabez will receive seven years of prosperity. Jabez signs with only minor hesitation. He quickly pays off his debts and buys his wife and mother clothes and jewelry. He also meets and befriends Daniel Webster, a man of integrity, who is also being pestered by Mr. Scratch with the offer of the presidency. Jabez is slowly changed by his wealth, alienating him from his wife and mother, and he begins to spend an unhealthy amount of time with a woman named Belle (who has been sent by Mr. Scratch, though Jabez does not know it). Jabez buys a mansion and hosts lavish parties, though one ends in tragedy when a man named Stevens (who was one of the misers holding Jabez down before his deal with Mr. Scratch) dies as a result of a deal with Mr. Scratch. This makes Jabez realize that his own time is nearly up and desperately attempts to get out of his contract with Mr. Scratch, but Mr. Scratch only offers to extend his contract for the soul of his son. Jabez refuses. Jabez begs his wife’s forgiveness and then pleads with Daniel Webster to help him. Webster agrees to defend him, but Mr. Scratch only allows a trial if Webster’s soul is also on the line. The trial is presided by John Hathorne (one of the judges during the Salem Witch Trials) and the jury of villains includes Benedict Arnold and Stede Bonnet. Webster argues that each man on the jury was in the same situation as Jabez at one time, which led to their downfall, but Jabez still has a chance to be free. The jury tears up the contract and Daniel Webster kicks Mr. Scratch out of New Hampshire. Mr. Scratch yells back at Webster that he will never become president.

The film is basically the story of Faust but with a nauseatingly American twist. It falls in line with a collection of other ridiculously Patriotic films that I can’t help but love, including Sergeant York, The Best Years of Our Lives, Top Gun, Rocky IV and The Patriot. Yes, All That Money Can Buy steers full-throttle into cheese in the last act, but you can’t help but love the unabashed “we can even beat the Devil” mentality. Honestly, though, what truly sets the film up to the standards of others is Walter Huston’s performance as Mr. Scratch. I admit, the only other movies I know Huston from are The Furies and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre – both movies that pull excellent performances out of him – but Mr. Scratch is his best role in my opinion. His blend of carnie, good ol’ boy, and used car salesman is the reason to watch this movie.