Eight Men Out is John Sayles’ take on the story of the 1919 Chicago White Sox – one of the greatest teams of baseball ever assembled – until they weren’t. It’s the all-too-true and sad story of a team, slighted by their benefactors, who decide their only way to get the pay they desire is to throw the World Series. Boxing and Gangster movies would have you believe that throwing games has been a constant practice in the world of sports, but in 1919 in America’s Pastime, it was unheard of.

Eight Men Out is also the ultimate “Oh, that guy’s in this?” movie. Some household names, like John Cusack and Charlie Sheen, as well as David Strathairn (practically in every John Sayles movie as well as Edward R. Morrow in Good Night, and Good Luck), D.B. Sweeney (Dish Boggott in Lonesome Dove and Travis Walton in Fire in the Sky), Don Harvey (bit roles in The Untouchables, Die Hard 2 and brief stint on General Hospital), Michael Rooker (McMasters in Tombstone, Yondu in Guardians of the Galaxy and Merle in The Walking Dead), Perry Lang (Jacob’s Ladder and Cattle Annie and Little Britches), James Read (North and South, Days of Our Lives, Charmed), Gordon Clapp (that guy from NYPD Blue), Bill Irwin (CSI, Northern Exposure), and Jace Alexander (…you know what, let’s not talk about him) round out the players. Richard Edson (Desperately Seeking Susan, Platoon, Good Morning, Vietnam), Christopher Lloyd (Great Scott! Do you really need his filmography?), Kevin Tighe (Emergency!), and Michael Lerner (the guy who thought it was a smart idea to have a pitch meeting for a children’s book on Christmas Eve in Elf) are the seedy gangsters and former ballplayers who claim a big payday if the boys throw the games. The floor walker from Cool Hand Luke and Fraser’s dad play the owner and manager of the team respectively. I guess you didn’t need to know all of that, but I think it’s fun.

Writer/Director John Sayles started off working under Roger Corman, a director who worked mostly outside of the studio system, except for a string of highly successful Edgar Allen Poe adaptations. For context of how important that is, here’s a list of filmmakers who were mentored under Roger Corman: Joe Dante, Peter Bogdanovich, Jonathan Demme, Ron Howard, Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and James Cameron. Impressive, innit? Sayles followed Corman’s way of self-financing his projects by writing genre scripts and using the paydays to fund his passions. So, the same guy who wrote and directed this movie, Passion Fish, Matewan, and Lone Star, also wrote a bunch of schlocky 80s creature features such as Piranha, Alligator and The Howling. The history lesson isn’t really necessary, but I’d always rather give my readers too much information rather than not enough. And I think John Sayles is an interesting director. Back to the movie.

After winning the American League pennant, the 1919 Chicago White Sox feel they are owed compensation, but the money-grubbing team owner, Comiskey, thinks they should be content with flat champagne. Seeds of discontent sow within the team, and that’s when wolves in former-baseball-player’s clothing swoop in and present an offer: lose the World Series on purpose and you’ll make more money than if you win. More powerful gangsters get involved, and it seems like a done deal. Some of the players, when faced with the proposition, balk at the notion and prefer the feeling of winning and playing your best, but others are all too eager to get what they think they should have already gotten from Comiskey. The de facto leader of the team, pitcher Eddie Cicotte, is on the fence at first, and goes to Comiskey to address a previous agreement that if Cicotte won 30 games in the regular season, he would receive a $10,000 bonus. Comiskey informs Cicotte that he only won 29 games and staunchly refuses. Equally motivated by revenge and a desire to provide for his family, Cicotte joins the conspiracy to throw the World Series.

Rumors float around as the Series begins, and with the White Sox’s initial performance against the Cincinnati Reds, it’s seemingly confirmed. The team manager, Kid Gleason, refuses to believe his players are cheating. Those who aren’t cheating are frustrated and fighting with those that are. Tensions and dangers mount as the gangsters start making threats against the players’ families. It’s really not a good time to be a White Sox fan…or player. After the Series ends, it only gets worse for the conspirators when a couple of journalists do enough digging to find evidence of their cheating. The players go trial, and despite being found not guilty, they are barred from Major League baseball forever.

Most sports movies are triumphant, feel-good experiences. Rocky goes toe-to-toe with Apollo Creed. Rudy plays a game for Notre Dame. Happy Gilmore saves his grandmother’s house. Kevin Costner gets to play catch with his dead dad. People remember the Titans. You get the idea. It’s much rarer to see a sports movie with a melancholic ending. These guys never got to play in the Majors again. One of the more innocent-but-still-not-totally-innocent-because-he-should-have-brought-the-conspiracy-to-someone’s-attention-if-he-knew-about-it players, Buck Weaver (John Cusack), sits at a minor league game, watching an incognito “Shoeless” Joe Jackson hit a home run and reminiscing on what could have been. It’s the what-ifs that make the story so interesting. What if Buck had said something about the conspiracy? What if Cicotte hadn’t chosen revenge? What if Kenesaw Mountain Landis (we really should bring back “mountain” as a middle name) had stood by the jury’s verdict or shone leniency? What if the conspirators had just said “no”? What if the players had just been compensated fairly in the first place?

Because of that approach, the film goes beyond the sport to shine a light on the unfair balance between those who did the work and those who reaped the benefits. And it was genuinely unfair. This was a long time before baseball players saw multimillion-dollar contracts. Owners were able to keep most of the earnings while maintaining low salaries for the players. Now, the film may not be 100% fair in it’s leaning towards the players. There are some things that we genuinely can’t be sure of. Was Buck Weaver as innocent as he claimed? Was Eddie Cicotte so concerned with money strictly for the sake of his family? Was the illiterate Joe Jackson really tricked into signing a confession of wrongdoing? These motivations, portrayed as black and white, are a lot grayer when looking at the real history. But in the end, it’s just a movie. And Eight Men Out is a fascinating one, to be sure.

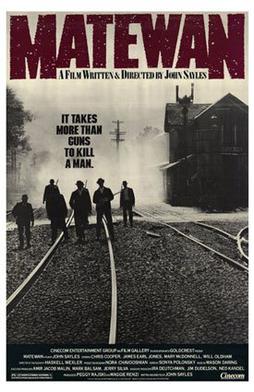

Bonus Review: Matewan

Eight Men Out was released in 1988. The year before, John Sayles released another historical drama called Matewan, named after the West Virginian town where the story takes place. In 1920, coal miners in Matewan go on strike against the Stone Mountain Coal Company after wage cuts. A man named Joe Kenehan (the woefully neglected and underrated Chris Cooper in his film debut) comes to town to encourage the miners to unionize. Soon after, two men from the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency arrive on a tip from a spy for the company within the town and attempt to frighten the strikers. When the townspeople refuse to leave, the detectives have to bring in backup. It culminates in what is known as the Battle of Matewan – a shootout between the coal miners and detectives working for the coal company.

Matewan is like Christmas – green and reds everywhere. The color grading of the film stock strengthens the greens of the trees and grass of Appalachia. It’s beautiful to look at, and rightfully received an Oscar nomination for Cinematography. The union organizer, Joe, is labeled by the detectives as a “red” – a Communist. Chris Cooper does a wonderful job for not only his first film role, but as the lead. He’s backed up by strong performances from David Strathairn and James Earl Jones.

I love the open-ended view of the politics in the film. Not everyone will agree with the pro-union message of the movie, but it does go out of it’s way to show that both sides escalate the tension and do more harm than good (the miner-supporting town sheriff starts the gunfight in the film, though in real life, no account of who fired first is made). Political messaging isn’t always the best reason for watching movies, however. Sayles’ historical dramas are informative replications of rarely-discussed events in American history. That alone makes them worth watching. Matewan makes a great double-feature with Eight Men Out mostly just to see more of Sayles’ filmography, but there’s a lot to say for the similarities between them in theme, in time period, and in actors (four of the actors are in both films). Both movies are timeless tales of timely situations.