It’s been awhile since I’ve done a list. I wanted to just stick to “Top 10’s”, but between this and my Top Westerns, I’m finding that to be a limit that I can’t stick to. Anyone who knows me will not be shocked by that fact. Anyway, enough about my shortcomings. Here are the Top 20 Christian Films, the criteria of which is simply whether it has a positive Christian message to it and whether or not it’s good. My apologies in advance to anyone expecting anything from PureFlix on here. Maybe when I do a Bottom 10?

20. Bruce Almighty

Bruce Almighty might be a head-scratcher for some. I remember when it came out it received some flack from Christian circles for making a mockery of God and Christianity, but I assume people who argued that didn’t watch past the first five minutes or didn’t watch the film at all. Bruce may be skeptical at first, and there’s no denying he’s intending to mock God when he decides he could do a better job, but the film is sincere in its take on faith and what Christian humility and service can do for one’s own spirit. The climax of the film is the most beautiful “field moment” (thank you, Say Goodnight Kevin) of any Christian movie ever – a “field moment” is that part of a Christian movie where the main character, at their wit’s end, walks out into a field, hands held high, and cries out to God in total surrender. The only difference is that, in Bruce Almighty, it takes place in the middle of a busy intersection.

19. First Reformed

Paul Schrader has never shied away from religious themes in his scripts, but First Reformed is one of his more obvious ones, as well as a blatant homage to another film on this list, Winter Light. We follow the pastor (Ethan Hawke) of a Dutch Reformed church in upstate New York as he struggles through a crisis of faith. His church attendance dwindles, death and suicide linger around him, others are concerned with the political climate rather than Christian stewardship. It’s enough to drag anybody down, and the reading of classic Christian authors, such as G.K. Chesterton, isn’t helping. It’s hopeless in Hawke’s mind, and he lingers so deeply in despair that his only solution is to go out with a bang. Much like Hawke’s pastor, by the end of the film, we are left with more questions than answers.

18. The Tree of Life

The first of two Terrence Malick films on the list. The Tree of Life is Malick at his most visually stunning. From the opening history of the earth sequence, to the above image towards the end of the three-hour film, there is not a wasted shot. Jumping between timelines, the film loosely follows the life of a boy growing up in Waco, Texas, as he grapples with the contending harshness of his father and the abounding grace of his mother – a personified battle between the Old and New Testament. Philosophical questions plague the boy, Jack, as he grows through his parents dichotomy and the loss of his innocence, until his adult life presents him a vision of the dead coming back to life, giving him a chance to say a final goodbye to his family. Brilliantly performed and unforgivingly experimental, this movie is all at once confusing and beautiful.

17. Sergeant York

Sergeant York was a conflicted man. He saw it as his patriotic duty to serve in the War, but it was his Christian responsibility to “not kill”. His solution, in the film, is to capture his enemies alive and march them all back to his camp…after he’s killed several. Made in 1941, Sergeant York is clearly American propaganda, encouraging everyone to do “the right thing” and get involved in the current war effort despite Christian misgivings, but it’s good propaganda. Gary Cooper is in perfect form as the “aw, shucks”, good ol’ boy, who’s a sharpshooter when it comes to turkeys, but the message of country-over-self keeps this from being higher on the list.

16. Ordet

Morten is a devout man who is struggling. He has lost his wife, his eldest son has no faith at all, his middle son thinks he’s Jesus Christ, and his youngest son is in love with a Lutheran – things couldn’t be worse. Weaving themes of self-righteousness, loss of faith, conflicts amongst different Christian sects, and the desire for faith when everything around you is crumbling into one film is a masterwork of one of the Danish greats, Carl Th. Dreyer. Ordet feels grander in scope and significantly more complicated, which is why it’s on this list over his more well-known film, The Passion of Joan of Arc.

15. Ben-Hur

Ben-Hur is a four-hour epic about a man who just wants to get back to his family. Judah Ben-Hur spends time in prison, as a galley slave, and a charioteer before successfully returning home. Throughout the trials that Judah Ben-Hur endures, he grows increasingly angry, fueling his hate for the man who betrayed him until it consumes him. Jesus Christ appears four times in the story, mostly in the background – his birth, a scene at a well where he gives Judah a drink of water, when he preaches the Sermon on the Mount, and his crucifixion, where Judah recognizes him as the man who gifted him water so long ago and attempts to return the favor. It is the crucifixion where Christ comes to the forefront, and acts as the ending to the film. At seeing Christ on the cross, Judah Ben-Hur’s rage dissipates.

14. Leap of Faith

In Rustwater, Kansas, Jonas Nightengale’s Travelling Salvation Show pulls into town. Accidentally. Their tour bus breaks down and they’re stuck in the dusty town for a few days. Nightengale (Steve Martin) decides to bring his big tent revival to the people in order to raise the money they need for parts. The town is ready to receive the Word. The only catch is Jonas isn’t a preacher- he isn’t even a Christian – he’s a conman out of New York City looking to make the big bucks with his faith healing shtick. Once he witnesses a true, honest-to-God miracle, his faith (or lack thereof) will be shaken to its very core. Slowly realizing the error of his ways, Jonas leaves town in the middle of the night, not wishing to feed the town anymore false gospel. On his way out, he witnesses another miracle and laughs, overcome with the joy of the truth he has discovered.

13. The Last Temptation of Christ

If you’re looking for a movie on the life of Christ, steer clear of this one. In fact, I don’t know if this is a film I’d recommend to most Christians. I’m sure you’ve heard the controversy surrounding The Last Temptation of Christ, so I won’t go into the details, but whatever you’ve heard of this film is probably true. The criticism from the Christian crowd tends to miss the point of it all, though. In the novel this film is based on, the author, Nikos Kazantzakis, prefaces it by saying that his intention was to play with the dual-nature of Christ. Yes, He was all God, but that means He was also all Man, and to think that Christ had to deny himself the life of a normal man – the life we all get to enjoy – makes his sacrifice all the more incredible, and that is something worth considering, even if both the novel and the film stray too far from the all-God side of Christ to emphasize their point.

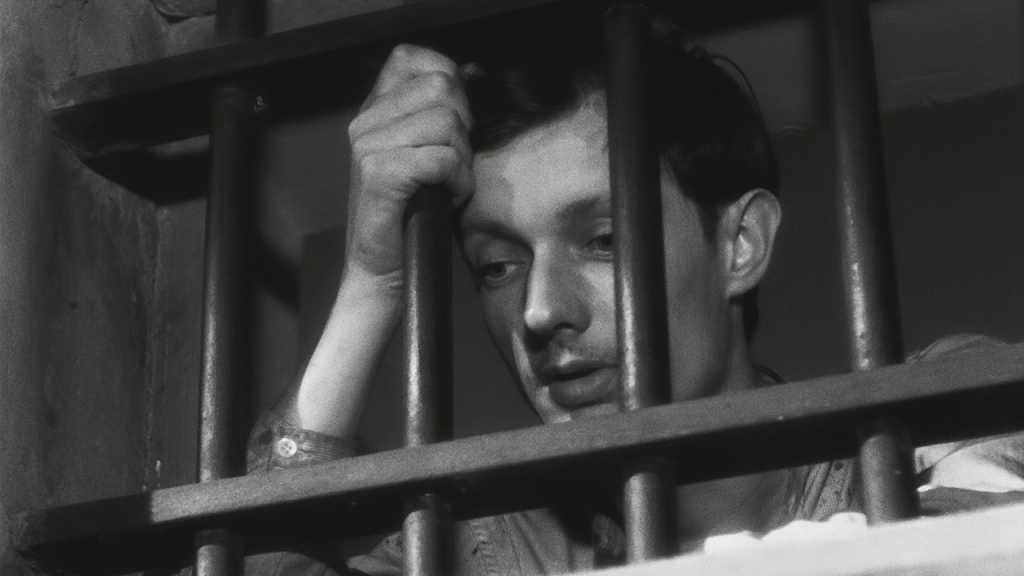

12. A Man Escaped

A Man Escaped is a POW film by the French director, Robert Bresson. Fontaine is a member of the French Resistance who has been captured and imprisoned by German soldiers towards the end of World War II. His days are spent mostly in solitude, occasionally chatting with one of the lucky prisoners who gets outdoors-time outside Fontaine’s window, or communicating with his neighbor in the next cell over. Fontaine has two things keeping him sane – the hope he has in his eventual escape and the hope he inspires in others, and both come from his unwavering Christian faith. He knows God will make a way for his escape, and it’s his fellow prisoners’ lack of faith that keeps them from joining him. This film is minimalist at its core, which may make the film seem boring to some viewers, but it’s deeply moving and its triumph is inspiring.

11. The Passion of the Christ

The main criticism of The Passion of the Christ is that it’s gore porn. I understand how that could be the view from an outsider, but I think the majority of Christians would agree that the violence showed on screen is the tip of the iceberg for what Christ endured during his trial and crucifixion. Displaying that horror in all of its gruesomeness is compelling and convicting, and necessary, if you want to do this part of the Gospel justice. More praise can be given for Mel Gibson’s use of unknown actors or the original languages used in the film (a particularly bold choice when most Americans are averse to subtitles by default). The film is a lot to take in, and it has a purpose in going to the extremes it goes to. Personal views of Gibson or Jim Caviezel aside, the message conveyed in this film is very basic and very Catholic, but it’s no less important for it.

10. Andrei Rublev

In the mood for a three-hour Russian biographical epic made by one of the most methodical film directors of all time? Understandable if you aren’t, but you’d be missing out on a beautiful piece of cinematic history. Which is not to say that it’s enjoyable to watch, but that’s more up to the individual. Andrei Rublev is set in the 15th century, and follows the titular painter through eight segments. Andrei witnesses horror and pagan violence, but also beauty on the handiwork of God in his trek across the Russian countryside. The film’s director, Andrei Tarkovsky, claimed the purpose of this film was to show “Christianity as an axiom of Russia’s historical identity”, and decides to end the film with a lengthy montage of Rublev’s work, showcasing the beauty in the religious experience.

9. Winter Light

The middle part of a spiritual trilogy from one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, Winter Light finds Ingmar Bergman at his most existential. This film is the clear inspiration for First Reformed, as it follows a preacher of a dying church as he seeks to console what remains of his flock, all the while having abandoned his faith, himself. This film is bleak and cold like the Swedish landscape it was filmed across, but it poses some very thought-provoking ideas, like the idea that the betrayal and confusion of his disciples and the silence of God while Jesus was on the cross is a harsher burden to bear than the physical torture he received. Bergman’s own history with faith (his father was a minister) gets put under the microscope for us to analyze. More vulnerable than wearing his heart on his sleeve, Bergman bears his soul to us.

8. Hacksaw Ridge

Hacksaw Ridge is Sergeant York without the propaganda. And involving a different war. Desmond Doss is drafted to fight in World War II, but his Christian morals prevent him from taking the life of another man. His goal is to become a medic so that he can comply with his country’s demands and stick to his moral code. His seeming self-righteousness makes him several enemies among his fellow soldiers, but he sticks to his beliefs in the face of such adversity and ends up saving those who hated him. He becomes a hero. It’s a little simple and straightforward, and most of the conflict is manufactured, but that doesn’t detract from what makes it great. The movie is a testament to unrelenting faith and a lack of compromise when trials come.

7. The Prince of Egypt

I don’t think anyone who has seen it needs to be convinced of how great this movie is. The animation is gorgeous, the voice acting is superb, and of course, the music is beyond amazing. A relatively faithful adaptation of the Exodus story, we follow Moses from his youth under the Egyptian Pharaoh to his time in the desert, and to his return to Egypt to lead God’s chosen people to their freedom. Sure, it pulls from The Ten Commandments about as much as it does from the Bible, but it tells its story without any compromise on the involvement of God or the harshness of His judgments. In fact, those judgments – the plagues – make for the best segment of the film.

6. Au Hasard Balthazar

When director Robert Bresson wanted to portray a character of pure innocence, he cast a donkey. This will make some people roll their eyes, I’m sure, but it’s accurate to the foundation of the Christian faith to say that, sometimes, people can’t cut it. Besides that, the personification of a donkey is scriptural, as is the opinion that the donkey is a humble beast of burden. The film revolves around Balthazar and the only human to ever show him any kindness, Marie. It’s a tragic story of sin’s abuse of innocence, and it culminates in one of the most beautiful final shots in a film ever. Au hasard Balthazar is not for everyone, and that’s okay, but you can’t do better than this film if you’re looking for a picture of the desolation of innocence in a sinful world.

5. The Mission

Rodrigo Mendoza is the worst kind of human being. He sells people into slavery, and he’s a Cain. He killed his own brother. He finds salvation through conversations with a Jesuit priest named Gabriel, who is in Paraguay, attempting to convert the natives to Christianity. He is successful with Mendoza, and somewhat successful with the natives, until political realignments in Spain and Portugal condemn the mission they call home and demand they move. Mendoza defends his newfound faith and home the only way he knows how – with a sword. The Mission is a testament to the strength of faith when it’s genuine and the detriment a wayward believer can have on a new convert or the overlap of politics and religion can have on entire groups of people.

4. Shadowlands

Based on a play, based on the true story of C.S. Lewis and his marriage to Joy Davidman, Shadowlands is an interesting perspective on romantic love and the plans of humans. It’s also a wonderful story of faith amidst tragedy. Lewis – “Jack” to his friends – meets Joy and immediately finds an intellectual equal. He’s intrigued by her, infatuated with her (in a sense), and when faced with reality that he will lose her, realizes he’s in love with her. It’s an unconventional love story and an excellent portrayal of all four types of love that Lewis ascribed to. It also contains one of my favorite quotes of all time. When questioned by one of his friends as to why he prays when he knows that the future is inevitable, Lewis says, “Prayer doesn’t change God; it changes me.”

3. A Hidden Life

Another film by the wonderfully poetic Terrence Malick, A Hidden Life is another true-story World War II film about a soldier that cannot reconcile his faith and his country’s demand that he fight and kill. The only difference between this film and Hacksaw Ridge – and it is a big difference – is that Franz is Austrian, meaning his country’s authority is Adolf Hitler, and Hitler’s less forgiving of defiance against country than Americans. The film covers a lot of ground, and even though it moves slowly, it earns its three-hour runtime. The film is a meditation on faith under God’s deafening silence and that is a theme that I think should be explored more.

2. Silence

One of Martin Scorsese’s absolute best films, Silence also explores the idea of God’s silence. However, in A Hidden Life, Franz never waivers in his commitment to his faith; in Silence, the Jesuit priest to Japan, Rodrigues, fails. He apostatizes when he is given the ultimatum from Japanese officials to either do so or witness the torture of innocents for his refusal. While Rodrigues does deny Christ to the Japanese government, he dies and is buried with a crucifix in his hand. The film proposes a very interesting thought: Is it okay to deny Christ (even in word only) if it means others will be spared? I don’t have an answer for that, but I don’t believe it’s as cut-and-dry as others might argue, and that’s what makes the movie so incredible.

1. The Gospel According to Matthew

What do you get when you give a copy of the New Testament to an atheist, socialist, homosexual Italian filmmaker? You get the most accurate film portrayal of a biblical story ever. This is not hyperbole. Whereas other films on the subject of Christ add dramatic embellishments or combine portions of the other gospels, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to Matthew is purely from its source. The dialogue is taken directly from the gospel account, and there are no “Hollywood” additions. To avoid the confusion of celebrity, Jesus is played by an unknown Italian man, and he is played with all the stoicism of a man uncomfortable with being in front of a camera. Pasolini’s motivation for the film is totally nostalgic for a belief he no longer has, if he ever did to begin with, and that distant desire for closeness frames the movie perfectly.