It’s almost my birthday, and since I’m a dull individual, I’ll probably spend it marathoning movies of my favorite genre; America’s genre: the Western. The characters, the wilderness landscape, crooked landowners, physical feats of strength and determination, psychological struggles, and personal moral codes – Westerns have it all in spades.

Because it’s probably my favorite genre, I had a very difficult time narrowing down my list for a Top 10. This Top 25 is the best I could do. This list is also definitive – if you disagree with any of the films on this list or their placement, you can safely assume that you’re in the wrong. Sorry, I don’t make the rules. Though I will admit, if you’re a fan of Western Comedies, there are some glaring omissions. Don’t worry, though. I’m saving them for later. Without further ado, put on your spurs and giddy up for the Greatest 25 Westerns of All Time,

25. The Sisters Brothers

The Sisters Brothers flew under the radar for most people. It’s a coproduction between America and France, and directed by Jacques Audiard, in his first English-language film. Based on a novel, The Sisters Brothers follows…the Sisters brothers, Charlie (Joaquin Phoenix) and Eli (John C. Reilly) – two assassins on the hunt of two men who have found a dangerous solution for panning for gold. The two leads play off each other well as the loose-cannon Charlie and at-the-end-of-the-road Eli, as well as Jake Gyllenhaal as one of the two panners. The film is a rambunctious adventure up to its blistering conclusion.

24. The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford

This 2-and-a-half-hour epic Western is also based on a novel. Unlike the previous entry, however, there are true events to back this one up. The Assassination of Jesse James is meditative and slow, but it’s beautiful and intelligent. Don’t let my title shorthand fool you, though. The film belongs to Robert Ford (Casey Affleck) – an outsider looking in on the fame that follows the leader of his gang, Jesse James (Brad Pitt). The camera captures the beauty of the landscape as well as the darkness creeping in to Ford’s relationship with James, and though we know how the story will end, the movie still keeps us enthralled the whole way through.

23. The Far Country

From 1950 to 1955, director Anthony Mann and James Stewart collaborated on eight films together – five of which were Westerns. Any one of them deserves a spot on this list, and it nearly came down to Winchester ’73 and The Man from Laramie, but I went with my personal favorite. In The Far Country, Stewart plays Jeff Webster, a cattle driver who makes his way to Alaska during the Yukon Gold Rush. When he crosses paths with the evil Judge Gannon (loosely based on real-life conman, Soapy Smith), the tension is palpable. It only rises as the movie goes on as Webster stops Gannon, scheme after scheme, until it comes to a boiling point – a one-on-one duel that turns into an ambush.

22. Thousand Pieces of Gold

Thousand Pieces of Gold is the sole feature film from director Nancy Kelly, which is a shame. She has such a strong grasp on the Western genre and the female perspective that it’s criminal that this film failed and cost her a career. Rosalind Chao (fans of Star Trek: TNG might recognize her) stars as Lalu, a Chinese woman who is sold to America by her impoverished family. In a Northwest mining town, she is bought to be a wife, then a prostitute, and finally, she is won in a poker game by a man named Charlie (Chris Cooper). With Charlie, Lalu is given the freedom to figure out who she is and create a better life for herself. This Western Romance is at times too sentimental, but it has a lot of heart.

21. Johnny Guitar

If you thought this movie would focus on a man named Johnny Guitar, you would be mistaken. The main character in this film is Vienna (Joan Crawford), the strong-willed owner of a saloon that is at odds with everyone else in town because she is okay with the railroad coming through and she lets outlaws and thieves patronize her establishment. Guitar (Sterling Hayden) is just the latest drifter who stops by for a drink, and luckily, he’s handy with a gun. The antagonism from the townspeople is spurred by Emma (Mercedes McCambridge), a jealous woman who wants to see Vienna dead by any means necessary. When one of the outlaws who frequents Vienna’s saloon rob the bank in town, Emma sees her chance to get her wish. The melancholic ending proves that Johnny Guitar is the ultimate Western Noir.

20. Little Big Man

Dustin Hoffman stars as Jack Crabb, or “Little Big Man”, a white man raised by Cheyenne, who has a foot in both camps. He’s lived a pretty remarkable life, having befriended Wild Bill Hickock and worked under General Custer. He’s also the only white survivor at Little Big Horn. A Western satire for the ages, this movie uses conflicts between Native Americans and white settlers as an analogue for the Holocaust and the Vietnam War. It’s also one, if not the only, film to portray both the Sand Creek Massacre and the Battle of the Washita River (which can only be described as a “battle” because Cheyenne warriors were present at the camp that the U.S. military attacked; it was still a massacre), although it makes no mention of John Chivington, a worse offender to Native Americans than Custer ever was.

19. Buck and the Preacher

This film is all at once a Western classic, a blaxploitation film, and one of the few media portrayals of “Exodusters”, post-Civil War African American settlers who went through hostile Native land and around white plantation owners to make a new home in Kansas Territory. This is Sidney Poitier’s directorial debut, and he also portrays our hero, Buck – a cowboy who acts as Moses to these Exodusters. Along the way, he runs into Reverend Willis Oaks Rutherford (a wily and devilish Harry Belafonte), whom he enlists to help him ward off a group of white raiders. Made just a few years after the end of the Civil Rights Movement, Buck and the Preacher is just as much fun as it is important.

18. The Ox-Bow Incident

The Ox-Bow Incident is the most unsettling Western you will ever watch. Henry Fonda and Harry Morgan play two cowboys who come to town just as news is breaking that a local rancher is dead and his cattle stolen. A posse forms to search for the murderers, and the cowboys join it. Just on the outskirts of the town, they find a trio of men who are unable to provide proof of purchase of the cattle currently in their possession, and so they decide to hang them at sunrise. However, over the course of the night, some men in the posse voice their doubts that these are the murderers they’re looking for. Just before sunrise, they decide to vote on whether or not to hang the three men. I won’t spoil the conclusion here. Suffice to say, this moody Western will grab ahold of you and not let go for days to come.

17. Dances with Wolves

Another directorial debut! This time it’s Kevin Costner behind the camera and in front of it as Lieutenant John Dunbar, a Union soldier who is perhaps a little suicidal. When he helps defeat a Confederate troop, he’s rewarded by being sent to an abandoned fort in Indian Territory. After a confrontation with the Lakota, Dunbar realizes his only chance for survival is to befriend his Native neighbors. Slowly, he integrates himself into their way of life, even taking one of their own for a wife. When he’s captured by U.S. military and charged with desertion, he must be rescued by his new tribe. Realizing he’s a danger to the Lakota with the military out looking for him, Dunbar goes into hiding, never to be seen again. With beautiful cinematography and a majestic soundtrack, this epic Western is a must-watch.

16. The Searchers

Ethan Edwards is the best acting of John Wayne’s prolific career. This isn’t to say there aren’t better movies with John Wayne in them, which this list will prove later, but Wayne is so perfect as the cynical, racist uncle to Natalie Wood’s Debbie, that no other performance comes close. When Debbie is kidnapped by Comanche, Ethan leads a small group to look for her and bring her home, or kill her if she’s been “tainted”. The most harrowing scene in the film comes when Ethan attempts to do just that after five long years of searching. Once he returns Debbie home, we watch through the doorway as Ethan Edwards walks out into the sunset. Not as a hero, reveling in his success, but as a bitter man refusing to accept that the world is changing without him.

15. Destry Rides Again

Tom Destry Jr. (a much younger James Stewart) is a sheriff who is unwilling to carry a gun. Not because he can’t handle one – he’s an excellent marksman – but because he would rather rely on his wit to bring law and order to town. He’s sent to Bottleneck when the previous sheriff goes missing, and in his absence, a crooked saloon-owner named Kent, and his girlfriend, Frenchy (Marlene Dietrich), have got the town in a stranglehold. It’s an uphill battle, but Destry is determined to win the respect of the townspeople and uncover the mystery of the missing sheriff. A riotous Western comedy in it’s own right, Marlene Dietrich’s Frenchy is the source of inspiration for Madeline Kahn’s character in Blazing Saddles, right down to the inability to sing and thick German accent.

14. The Good, the Bad & the Ugly

I mean, what is there to say? You know the movie, you know the score, you know the Mexican standoff scene. Considered the ultimate Spaghetti Western, The Good, the Bad & the Ugly follows three men -the quiet Blondie, the venomous Angel Eyes, and the oafish, double-crossing Tuco – in search of a cache of Confederate gold. With bounty hunters and U.S. military hot on their trails, they must, at times, work with each other and against each other if they’re going to find the grave where the gold is buried. This film was an international success, making Clint Eastwood a mega star and introducing the United States to Lee Van Cleef and Eli Wallach. It also happens to be Sergio Leone’s masterpiece.

13. The Big Country

This is not the last time you’ll see Gregory Peck playing a pacifist seeking peace in an unruly West on this list. But this is the only time you’ll see it in Technicolor. The Big Country is an epic Western centered on a Hatfields and McCoys-style conflict between two families – the Terrills and the Hannasseys – with Peck’s James McKay caught in the middle. McKay is a wise man, who sees the folly of the rivalry, and refuses to let either side goad him into their foolishness. His desire for peace above all costs him his fiancée, Patricia, the daughter of the Terrill patriarch. McKay’s desire for peace is proven right as the confrontation between families comes to a tragic head. A morality tale with fantastic supporting performances from Charlton Heston and Burl Ives, this film, like Gregory Peck, is unwavering.

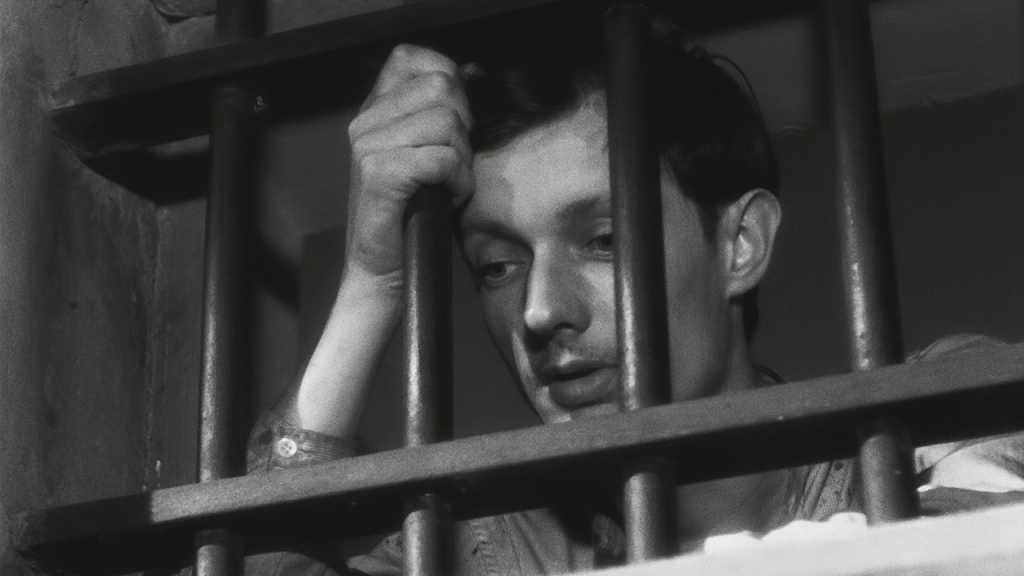

12. Stagecoach

Stagecoach did more for the Western genre than any other film. It imbued John Ford with his love for wide shots in Monument Valley, it made John Wayne a superstar lead actor, and it brought the Western out of B-Movie Hell and brought it to a place of prominence and prestige. You’ve probably seen some variation of this movie before: A group of strangers meet on a stagecoach as they make their way from Arizona to New Mexico. They have a multitude of reasons to make the trip – a fresh start, meeting family, vengeance – and they have to brave through Apache territory to get there. Along the way, John Wayne’s Ringo Kid, who has busted out of jail to kill the men who murdered his father and brother, falls in love with Dallas (Claire Trevor), a prostitute that has been kicked out of town and must now find somewhere she’s accepted. Action, romance, and great characters – this movie has it all.

11. The Gunfighter

Gregory Peck is Jimmy Ringo, the Gunfighter. Weary of his gunslinging lifestyle and tired of being viewed as an outcast or some kid’s ticket to fame as “the man who shot Ringo”, he decides it’s time to retire and become a respectable member of society. He returns to Cayenne, the town where his wife he hasn’t seen in eight years and the son he’s never met live. Through mutual friends, Ringo is given the chance to plead to his wife to join him in California, but she asks for a year to consider it and see whether he stays out of trouble. At the urging of the marshal, Ringo decides to leave town, but it’s too late. The brothers of a young man Ringo shot and killed in self-defense have arrived and are waiting to ambush Ringo. This film’s conclusion is a meditation on the price of fame and the circular perpetuation of an eye-for-an-eye.

10. Red River

John Wayne is Thomas Dunson, a man who wants a wife, a cattle ranch, and a son. When an attack on the wagon trail deprives him of his wife, Dunson decides to adopt the only survivor of the attack as his son. Fourteen years later, the cattle ranch is a success, but Dunson is a broken and wearied man. He decides to drive the cattle to Missouri in order to sell them and he brings his team, including his adopted son, Matt (Montgomery Clift), along with him. Dunson is a tyrant on the trail and eventually, Matt and Dunson’s men revolt, taking the cattle to Kansas instead. Not one to let any slight go unpunished, Dunson follows their trail. There is plenty of action and romance in Red River, as well as an excellent critique on generational sins and manhood.

9. Cat Ballou

Catherine Ballou (Jane Fonda) is a schoolteacher who returns home to her father’s ranch only to discover that the Wolf City Development Corporation is threatening Frankie Ballou (John Marley) to give up his ranch so they can use it for their own purposes. When Frankie refuses to give in to their demands, they send the killer, Tim Strawn (Lee Marvin), to do what he does best. Cat hires the notorious sharpshooter, Kid Shelleen (also Lee Marvin), in an attempt to save her father, but Shelleen is revealed to be a drunken buffoon – still a crack shot, but past his prime. After the murder of her father, Cat Ballou demands justice from the town of Wolf City, but she doesn’t get it. With a ragtag team, she decides to take matters into her own hands, becoming a notorious outlaw. When she accidentally kills the head of the Wolf City Development Corporation, she finds the town now all too willing to pursue justice. It’s hard out there for a woman. This Western Comedy is equal parts hilarious, dramatic, and action-packed, and Lee Marvin shines as the uproarious Kid Shelleen. There’s also Nat King Cole and Stubby Kaye as two banjo-wielding minstrels to narrate the story.

8. High Noon

Will Kane (Gary Cooper) is getting married when it’s announced that Frank Miller is on the twelve o’clock train, headed for town. This is a problem for Kane, since Miller is a vicious outlaw and Kane is the town’s marshal, and Kane was the one to put Miller behind bars in the first place. He now sees it as his responsibility to do so again. Miller’s gang, including his younger brother, are waiting for Frank at the train station, and when they arrive in town, it will be a very unfair four-against-one. Kane pleads with the town judge, mayor and all his friends in town to help him take care of the Miller gang, but everyone has one excuse or another, except for a fourteen-year-old boy who Kane rightly sends on his way, despite his appreciation of the boy’s courage. His own bride, Amy Fowler (Grace Kelly), urges him to abandon the town, and when he refuses, she abandons him. Come high noon, it’s an empty street as Kane and the Miller gang close the gap between them. This movie plays out in real-time, which increases the tension drastically. High Noon is mostly famous for a great performance by Gary Cooper and being an allegory of the McCarthy era Hollywood Blacklisting. It’s also responsible for its two biggest detractors, Howard Hawks and John Wayne, to make Rio Bravo – a vastly inferior film, but still considered a Western classic.

7. The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

For the record, the actual quote is, “Badges? We ain’t got no badges. We don’t need no badges. I don’t have to show you any stinking badges.” Doesn’t roll of the tongue as well, I know, but I wanted to clear the air. Fred Dobbs (Humphrey Bogart) and Bob Curtin (Tim Holt) are down-on-their-luck drifters when they hear about gold prospecting in the Sierra Madre mountains. Considering their one-off employers seem to have a bad habit of forgetting to pay the two men for their work, they happily go in with a seasoned prospect named Howard (Walter Huston). When they successfully discover gold dust in the mountains, bandits and Federales are the least of their concerns. The real enemy to watch out for is their own unbridled greed. Yes, it’s an old morality tale you’ve heard thousands of times, but no retelling of that tale is as engaging as The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. Twists and turns, double-crosses, and parasites are around every corner, and you can never guess which direction the film will go at any given moment. It’s that kinetic spontaneity that will keep the film with you years down the road.

6. Django Unchained

A German bounty hunter/dentist named Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) seeks to purchase a slave named Django (Jamie Foxx) because he should recognize the faces of his next big score, the Brittle Brothers. The deal is if Django can point them out to Schultz, then Django is a free man. As they track down the Brittles, Schultz gives Django the opportunity to learn to shoot and read, where he proves to be a natural at both. After they successfully kill the Brittle Brothers, Schultz learns that Django was married to a house slave named Broomhilda (Kerry Washington) before they were sold separately and is determined to reunite them. They find Broomhilda or “Hildi” is a slave at the plantation of Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio), and come up with a ruse to get Candie to sell Hildi to Schultz. The main house servant, Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson), discovers the nature of Django and Hildi’s relationship, and alerts Candie. Multiple gunfights ensue and it’s going to require all of Django’s wit to get out of Candie’s plantation with Hildi alive. Quentin Tarantino is not for everybody. I’m well aware of that, but if you can look past his overindulgences, you can find a charming, action-packed, and surprisingly hilarious send up to Spaghetti Westerns in here. The movie has intensity and swagger, and a multitude of well-defined characters in spades. Django Unchained is one for the ages.

5. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

Upon entering the town of Shinbone, Rance Stoddard (James Stewart) is immediately attacked by the outlaw, Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin), and his gang. Rance is discovered by Tom Doniphon (John Wayne) who carries Rance in to be treated for his wounds by his girlfriend, Hallie (Vera Miles). Rance works in Shinbone, hoping to set up a law practice, befriends the local newspaper editor, Dutton Peabody, and decides to build and teach a school when he discovers Hallie and a good portion of the town are illiterate. Meanwhile, Valance’s tirades on Shinbone and the surrounding area are getting worse, and Rance decides he better learn to use a gun. Tom attempts to teach him, but soon their time together turns into a competition for Hallie’s affections. When Rance finally confronts Valance, Valance quickly disarms him and aims to kill. Rance reaches for his gun and fires and Valance goes down. Unbeknownst to everyone else, Tom is standing in the bushes with a rifle. Which one was the man who shot Liberty Valance? In the end, it doesn’t seem to matter. “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is the best film John Ford ever made. It plays into the personalities of its lead actors, but also treats the material with the respect it deserves. It’s a statement – a bold exclamation point on the careers of three Western filmmakers.

4. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

Butch Cassidy (Paul Newman) is the fun-loving leader of the Hole-in-the-Wall gang, and Sundance (Robert Redford) is his quiet, crack shot right-hand-man. Together, with the rest of the gang, they successfully rob a couple of trains, but that alerts the attention of the head of Union Pacific, who sends a posse of lawmen after them. Cassidy convinces Sundance and Sundance’s girlfriend, Etta Place (Katharine Ross), to hide out in Bolivia, which Cassidy inexplicably assumes is an outlaw’s paradise. However, they are soon deprived of that fantasy upon their arrival. Sundance particularly loathes the place. Due to their inability to speak Spanish, they are initially unsuccessful at robbing banks, so they consider quitting the criminal life for good. Their first day as honest-working men ends with their boss being killed by bandits in a shootout. They decide the honest life isn’t for them, and return to their old ways. When they arrive in a small Bolivian town, they are met by the local authorities who have also called in the Bolivian army to help bring down Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. The two friends go down in a blaze of glory and the film ends with the greatest freeze-frame of all time (although, Thelma & Louise gives it a run for its money). The chemistry between Paul Newman and Robert Redford is magnetic, so much so, between this film and The Sting, they are considered one of the greatest on-screen duos of all time.

3. True Grit (2010)

I had to specify the year because I imagine some of you erroneously believed that the original 1969 film would be on this list. If you can handle Glen Campbell and Kim Darby’s acting, more power to you, but for me, the 2010 Coen Brothers version is infinitely superior. Even if you believe that John Wayne is Rooster Cogburn, you can’t deny that Jeff Bridges is the better actor. The Coen Brothers version leans into the quirkiness of the original novel by Charles Portis, and toes the line between humor and action, while keeping the intensity and theme of fruitless revenge intact. If you don’t know the story, Mattie Ross (Hailee Steinfeld) is a strong-willed girl who doesn’t have the time or patience to leave justice against the man who killed her father to anyone else. She pursues Tom Chaney (Josh Brolin) herself, and seeks the assistance of Marshal Rooster Cogburn (Jeff Bridges) to help bring him down. Cogburn is a drunken shell of the man he once was and so doesn’t appear to be much help, but he makes the attempt anyway, and they add Texas Ranger LeBoeuf (Matt Damon) to the mix. At every turn, every person including Cogburn and LeBoeuf tell Mattie that this is no venture for a young girl, but she’s determined. Once they find Tom Chaney with the Ned Pepper gang, she and Cogburn both get the chance to prove their mettle. Bite down and your leather reins and get ready for one of the most glorious finales ever put to film.

2. The Magnificent Seven

The only difference between Westerns and Samurai movies is location, and this film is the proof. The three-hour epic from Akira Kurosawa, Seven Samurai, is the film The Magnificent Seven is based on, and the two are basically equal in their impact. Seriously, how often is a remake as good (or at least pretty close) as the original? This film is packed with an all-star cast. Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson, James Coburn, Robert Vaughn, Brad Dexter and Horst Buchholz are the titular seven, and Eli Wallach is their opposition, the leader of the bandit gang terrorizing the poor Mexican villain, Calvera. These seven gunslingers are hired by the village to defend them from Calvera. The fear of the villagers and circumstances eventually cause the seven gunfighters to second-guess their decision to help them. However, when Calvera attacks the village again, the seven rally together and defend the people who have slighted them. In the melancholic ending to this magnificent film, Chris Adams (Brynner) muses that the villagers won the day, but the nature of the gunfighter is to always lose. Great performances, a beautiful backdrop, and one of the greatest film scores of all time are the pillars of this remarkable remake of a foreign film. It’s also a loose inspiration for the plot of the Western Comedy, Three Amigos.

1. Tombstone

If you know me very well, there’s no way you’re surprised this is at the top spot. Tombstone is the movie that got me into Westerns. It’s the story of the Earp brothers, Wyatt, Virgil and Morgan, and their friend, John “Doc” Holliday, their confrontations with the red-sash-wearing Cowboys, building to the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, and culminating in the notorious Earp Vendetta Ride. Wyatt Earp (Kurt Russell), already a famous lawman from his time in Dodge City, joins Virgil (Sam Elliott) and Morgan (Bill Paxton) in the booming town of Tombstone. They establish themselves as runners of a faro table in local saloon, and run into Wyatt’s good friend, the hard-smoking, hard-drinking, hard-gambling Doc Holliday (Val Kilmer). They also meet Bill Brocius (Powers Booth), an important member (and soon to be the leader) of the Cowboys, and Johnny Ringo (Michael Biehn), his best gunman who sees himself as the Fourth Rider of the Apocalypse. When the Earps begin to do what the law won’t do and serve justice, the Cowboys don’t take kindly to it. The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral ends in several Cowboys dead at the hands of the Earps, and the Cowboys retaliate, killing Morgan and wounding Virgil. Wyatt decides to wipe out all remaining Cowboys to finally achieve peace, and Holliday, despite his tuberculosis getting worse and making him bedridden, joins the posse. Thus begins the ultimate showdown, and the best gunfighting montage in all of cinema. A crackling script with dialogue taken directly from the late 1800s, true horse and gun play, wonderful performances, and real moustaches keep the film authentic and exciting. There are cameos and supporting roles from Chalton Heston, Billy Bob Thornton, Billy Zane, Jason Priestly, Stephen Lang, Michael Rooker, and a narration from Robert Mitchum. Above all, there is a once-in-a-lifetime performance from Val Kilmer who embodies the legend of Doc Holliday that anchors the film. “Greatest Western of All Time” hardly does it justice.